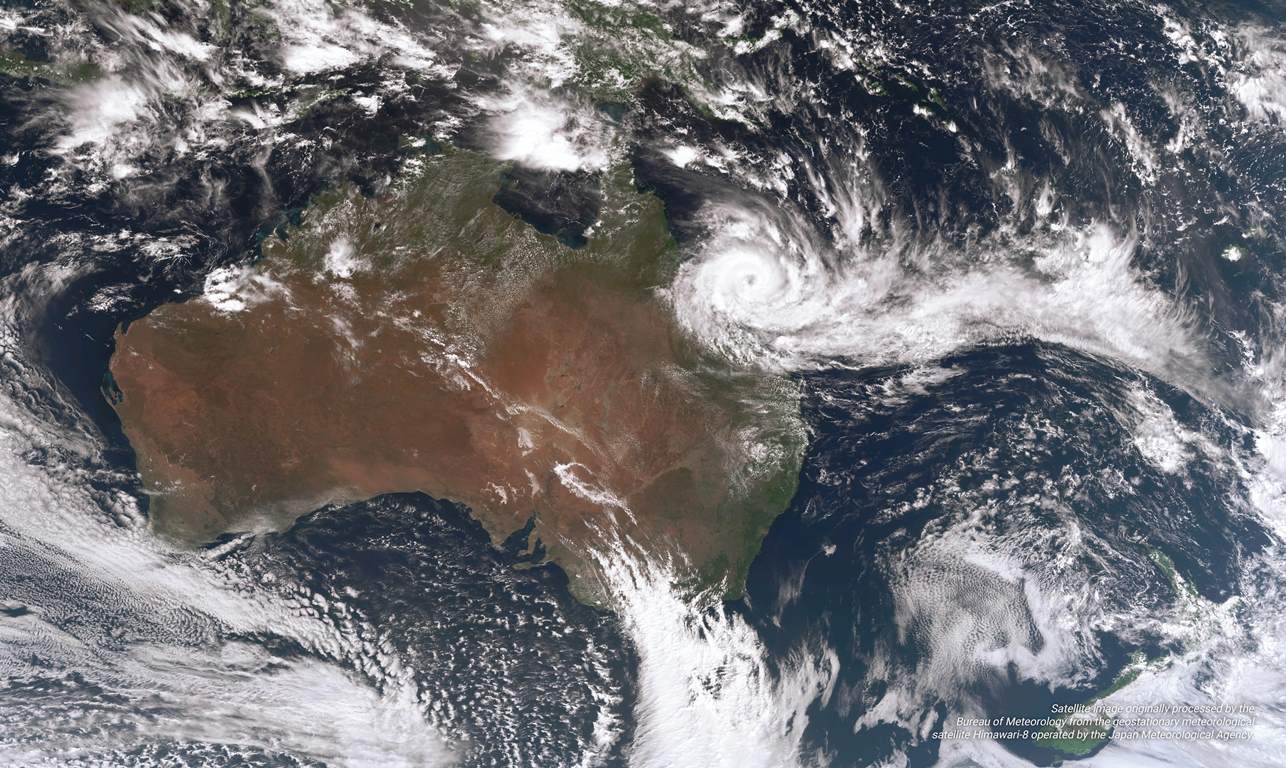

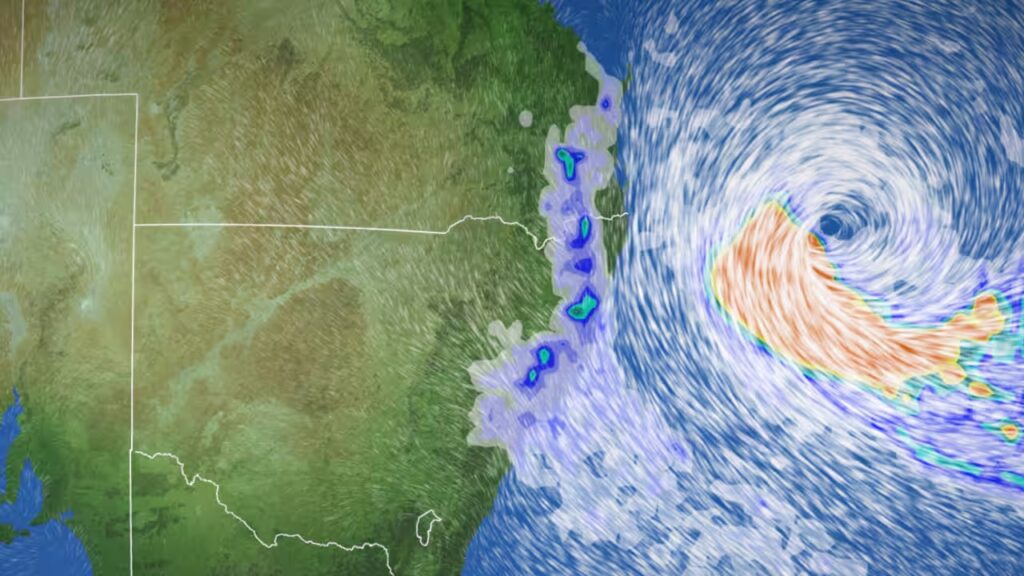

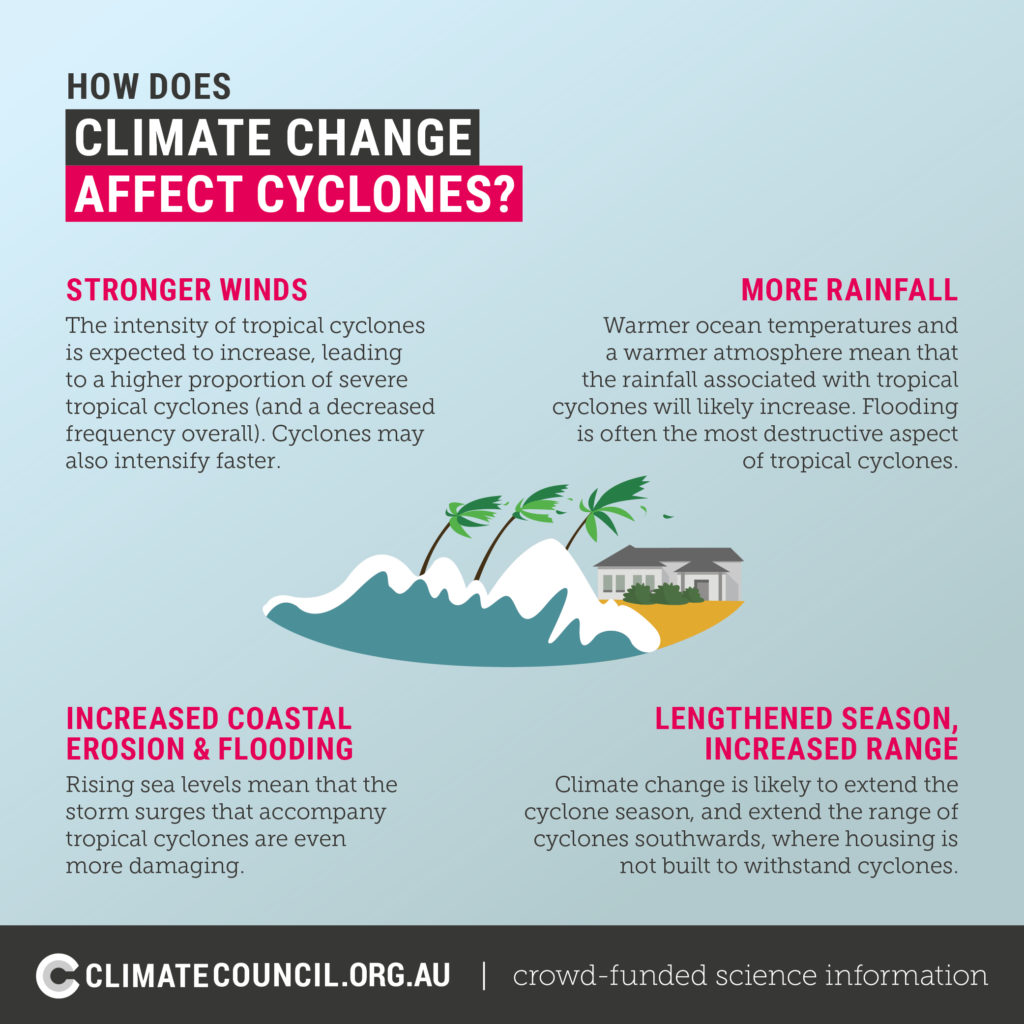

In our changed climate, when tropical cyclones form they form in a climate that is warmer, wetter, and more energetic than before. This means tropical cyclones may intensify more quickly, may reach stronger wind speeds, and may dump more rain. They may also retain their strength for longer, and move more slowly – meaning they linger longer over a given area, causing more damage. Riding upon higher sea levels, they may also bring even more dangerous storm surges and coastal flooding.

Tropical cyclones have always been part of life for many people in Australia and the Pacific, but climate change is making them more destructive.

Tropical Cyclone Jasper, which hit northern Queensland in December 2023, was only a Category 2 system when it reached land, but showed many of the characters we’ve been warned to expect of cyclones as the world warms: It was very early for a cyclone during an El Niño event, moved slowly, lasted a long time, and brought extraordinary amounts of rainfall, leaving many communities stranded by floodwaters. Tropical Cyclone Yasa, which ripped through Fiji’s northern island of Vanua Levu in December 2020, was similarly unusual. It was the earliest category five South Pacific cyclone on record, intensified very rapidly, brought extremely high winds and rainfall, and moved slowly – causing tremendous damage as it lingered for many hours over Vanua Levu.

Predictions for the future

The total number of tropical cyclones will likely decrease in the future, since their formation is favoured by greater temperature differences between a warm ocean and a cold atmosphere (a gap that will be reduced by a warming climate). But those tropical cyclones that do form, however, will likely be more severe due to the reasons outlined above.

Find out more about our summer so far and the impacts of El Nino here.

Learn more in our updated factsheet on Tropical Cyclones and Climate Change, including the latest science on the influence of climate change on tropical cyclone formation and behaviour.

Want to be the first to find out about the latest climate news? Join the Climate Council today.