Climate change is no longer looming on the horizon. The intensification of extreme weather events—heatwaves and extreme heat—is being felt in our streets and homes, and for the million people living in Western Sydney whose sleep, school, and work are suffering the brunt, it’s becoming hard to live.

Since records began, Australia has warmed by around 1.44˚C and is getting hotter, but the heat isn’t felt equally: few places are suffering so severely as in Sydney’s western suburbs. January 4th 2020, Penrith was the hottest place on Earth at 48.9˚C (half-way to boiling point) and in 2019 Parramatta sweltered through 47 days with temperatures over 35˚C.

These hostile conditions are unnatural. They are the reality of climate change compounded by slapdash urban planning, short-sightedness, and a rapidly growing population that has sent heat-intensifying infrastructure (roads, homes, carparks) sprawling into the Cumberland Plains.

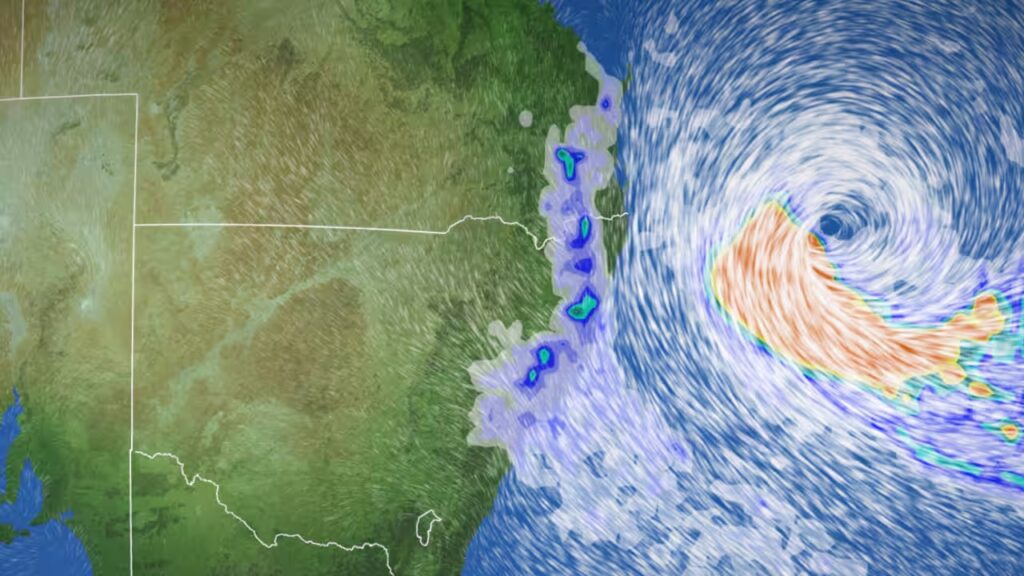

The summer 2019/20 temperatures in Jordan Springs, near Penrith, an area suffering from the urban heat island effect. Image: Dr Sebastian Pfautsch.

“Western Sydney is one of the fastest growing—perhaps the fastest growing urban population anywhere in Australia. The mistakes [in urban design] being made in Western Sydney are being made in Melbourne, Brisbane, Perth. We’re not really thinking ‘How do we deal with the changing climate, particularly heat?’,” says Dr. Sebastian Pfautsch, Associate Professor of Urban Studies at Western Sydney University.

He describes the side-effects and challenges of overheated suburbs: from strains on public health, to economic instability, and low community cohesion.

“It wasn’t even summer yet,” he says of spring 2019, “and we had a heatwave approaching where the energy providers were looking at the network thinking ‘Will it actually collapse?’ Think about 2030 or 2050 when we have 800,000 more people living in Western Sydney.”

It’s not just about energy consumption and population figures. Extreme heat is undoing the fabric of everyday life and the things we take for granted, like a childhood at the playground or being able to go for a walk.

Extreme heat and children

With their parents at work, many young children in Sydney’s western suburbs spend the day at kindergartens or remain with their grandparents.

“Playgrounds at public parks may be children’s only regular access to nature. It’s the place where kids’ gross motor activities take place,” says Sebastian, “—more than running from one room to another; it’s exercise, risk management, self-awareness, learning compassion for other humans and nature.”

He describes the cognitive and physical qualities that need to be imparted to children and the critical window in which these things must develop, from 18 months to 7 years old. “It’s absolutely key that these things happen in playgrounds.”

“But we’re building playgrounds without shade and the wrong surface materials, and that means—with increasing summer heat—we can use these playgrounds less and less. Sadly, this applies to the majority of play spaces in kindies and parks.”

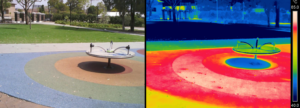

A playground in Auburn seen with the human eye versus temperature-sensitive camera. Image: Dr Sebastian Pfautsch.

By constructing playgrounds by the letter without regard to local conditions, the usability—and safety—of equipment goes up in smoke. Recording the temperature of playgrounds during summer, Sebastian regularly logs surface temperatures upwards of 80˚C. Play equipment conducts heat like cutlery in an oven and can be hot enough to sear skin. The rubber play surfaces can reach above 100˚C; there’s no need to imagine the ground being lava. “We need [playgrounds] to help these new citizens become Earth stewards…but we’re seeing a shift indoors.” In a changing climate, hot days will get hotter and these realities will worsen.

“Diabetes and obesity are already at a high rate in Western Sydney. Most of the kids are riding in cars due to shops or schools being so far away. Parents drive in their air-conditioned cars out of their air-conditioned homes into the air-conditioned shopping malls. You can’t walk outside, particularly in summer, because there’s no shade. The whole urban design of transport, which might encourage active transport like riding a bike, is done very badly.”

Urban heat and deteriorating education

But perhaps more alarming than extreme heat in playgrounds is the extreme heat present before and after the summer break—while kids are still at school.

“Looking at Bureau of Meteorology data we know that ambient heat during school days in summer is rising. This means if you have no air conditioning, you see more days of high classroom temperatures too. You learn less in these classrooms. We have very compelling data on how heat is impacting learning outcomes. A massive study from the US shows that for every 1˚C increase in annual average classroom temperature, there follows a 2% loss in learning outcomes. We shouldn’t accept that.”

Sebastian compares kids in the overheated western suburbs with no air conditioning with those in other more prosperous waterside-cooled areas, and imagines the effect of heat played out for five years.

“You can calculate how much less a child will learn by the time they’ve reached their HSC.” Children with identical IQs and educated in different locations will diverge and wind up in a very different place by Year 12. “We have federal laws that prescribe fair and equal learning conditions for children across Australia, and yet we’re not delivering on that, not anywhere near it.”

Western Sydney and reducing the urban heat island effect

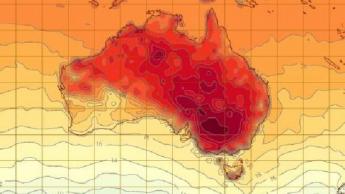

Under a changing climate we can all expect an increase in the frequency, intensity, and duration of heatwaves, but why is it they’re so immediate and severe out west? To begin with, the features that naturally reduce heat have been removed and replaced with man made structures that magnify it.

Trees are a natural defence against the heat—with leaves to rebound sun and shade surfaces, and water vapour to cool the air—but are swapped out for low maintenance landscapes. Green spaces, such as parklands, absorb and dissipate heat but have been replaced by buildings of bricks, cladding, metal and glass. Waterways such as lakes and rivers, that act like temperature buffers to convert heat to cooling vapour, are replaced by winding asphalt roads and expanses of concrete in car parks that can reach 80˚C surface temperatures.

Sydney’s Central Park building whose hard and gleaming surfaces are partially offset by green space, which works to reduce heat. Image: Creative Commons/Flickr/AndyM5855

It’s the buildings and roads and other sealed surfaces—which, Sebastian has calculated, cover 80% of some suburbs—that are so subtly damaging. Their hard surfaces generate more heat than we can withstand, and it’s heat that’s guaranteed to be magnified by more thoughtless urban sprawl. Hard surfaces act like sponges, absorbing heat from the sun during the day and releasing this stored energy during the night. The heat leaks out throughout the night, preventing suburbs from cooling down to safe levels and thus placing the health of residents at risk.

Hospital admissions speak a clear language: rates of morbidity and mortality increase well above the norm during a string of two to three extremely hot nights. It’s not just the daylight hours of a heatwave but also the nighttime residue that is the killer. Since 1890, heatwaves have killed more Australians than bushfires, cyclones, earthquakes, floods, and severe storms combined. These are the costs and consequences of climate change, which have been gathered and summarised in our report ‘Hitting Home: The Compounding Costs of Climate Inaction.

Reducing the urban heat island effect

The key is to incorporate ‘open space’, or rather, undeveloped natural areas, into our cities.

“What we could do right now to stop creating more hot suburbs,” says Sebastian, “is to build heat-smart density and build upwards. Apartment buildings of five to fifteen storeys arranged in clusters that shade each other, no more free-standing homes. This clustered housing supports two or three thousand people, and then around that you leave the space open: parklands, lakes, recreational facilities, picnicking areas where community can actually happen.”

Solutions can occur—need to occur—at a micro local scale, too.

In 2020 Sebastian and partners from government and industry developed and introduced a UV Smart Cool Playground to Cumberland Council with shade covers and heat-reducing polymer play surfaces, making equipment ‘playable’ once more—halving temperatures experienced by children. It’s these types of ‘demonstration’ sites that are so valuable, where people can experience the alternative. Life in Sydney’s west does not need to be inhospitable.

Climate change and adaptation: living with the heat

“I’m measuring air temperatures in Western Sydney that are over 50˚C. Will it be 55˚C at some point? The heat that we have to deal with, which is projected to increase for decades to come, is already here. The region is becoming uninhabitable during summer, and this is where the new arrivals are expected to settle, build and bring up their children.”

While the effects of climate change are already making large tracts of Western Sydney uninhabitable, there is much we can do. As individuals, Sebastian suggests to “plant a tree, make your next car a hybrid or go electric, paint your roof with a cool paint, insulate your house,” but change needs to be made at every scale of society.

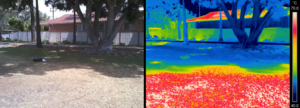

The cooling effect exerted by trees as exemplified in a South Granville park, the shaded area beneath the tree being some twenty degrees cooler. Image: Dr Sebastian Pfautsch.

Extreme heat also needs to be addressed at its root cause: climate change. The Federal Government needs to step up and take charge of the country’s future. Temperatures are rising, and will continue to rise, and the quicker we can move beyond fossil fuels to reach net zero emissions, the quicker that rising heat can be capped. Until then, those living in vulnerable areas will continue to cop ever-escalating impacts, the disproportionate exposure and excesses of extreme heat, until real and effective action is enacted by the government.