We have been installing wind and solar power projects in Australia since the 1980s – and now, more than 40% of the power in Australia’s main grid comes from renewable sources. As we continue to roll out more renewables, many of us are wondering: what will happen to all these wind, solar and battery projects once they reach retirement age?

Just like any technology, renewables have a lifecycle and at some point will reach the end of their operational life. However, when renewables reach retirement age, that doesn’t automatically mean they have to be decommissioned. Projects can be refurbished or repowered to extend their lives. If a project does need to be decommissioned, the land and soil can be returned to their previous condition without risks to the environment or public health, and more than 90% of the components of wind turbines, solar panels and lithium-ion batteries can be recycled to further reduce the environmental impacts.

RE-Alliance – a leading voice on regional perspectives in Australia’s shift to renewables – has done a deep dive into the current landscape of retirement age renewables in Australia. They have also developed a toolkit to provide information in clear, plain language to help landholders, communities and local councils understand what happens when renewable energy projects reach retirement age.

We’ve looked at RE-Alliance’s resources to help answer eight key questions about retirement age renewables.

Tom Gunthorpe on Future planning with renewables, Video credit RE-Alliance

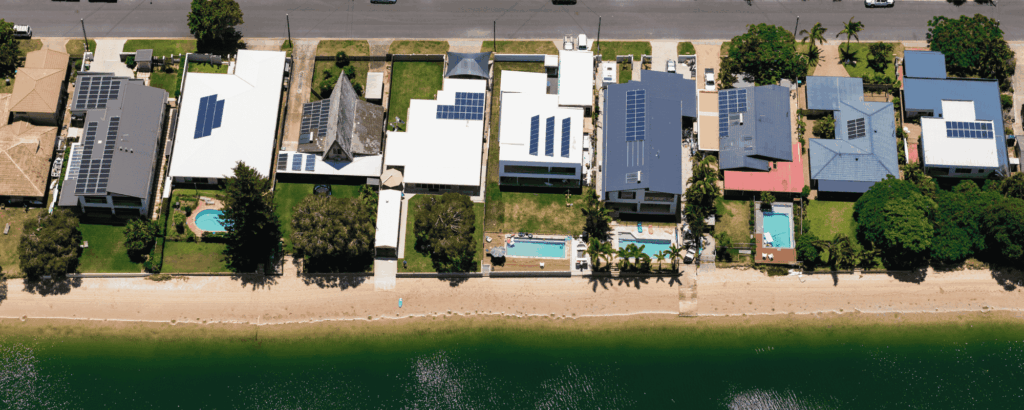

What is the lifespan of a renewable energy project?

An onshore wind farm is expected to be operational for between 25-40 years, while the lifespan of a solar farm is up to 25 years.

However, the lifespan of an individual project will depend on many factors. Many of the older renewable projects in Australia are already exceeding their expected lifespan: our oldest large, grid-connected wind farms were originally expected to operate for around 20 years, but they are still running and are now expected to last around 30 years.

This chart outlines the anticipated retirement ages of renewable technologies.

What are the options for retirement age renewables?

There are three main options for managing a renewable project that is reaching its end of life:

- Refurbishment (or life extension): Upgrading components of the existing assets and infrastructure at a renewables site to newer components.

- Repowering: Replacing old technology on the same site with newer, more efficient models, usually with a higher output.

- Decommissioning: Completely dismantling the assets and associated infrastructure, removing equipment, and rehabilitating the site, as agreed with the landholder.

Is renewable infrastructure recyclable?

Nearly all of the components that make up wind turbines, solar panels and lithium-ion batteries can be recycled. If a project is decommissioned, or if old technology is removed and replaced with newer infrastructure, all the old infrastructure will be removed from the property. Nearly all of the parts can be reused or recycled, preventing them from ending up in landfill and reducing the amount of ongoing mining needed for the metals and critical minerals used in these technologies.

- Wind turbines are more than 90% recyclable, and Australia has high capability in metals recycling that we need to achieve this. Turbine blades, which are traditionally made of composite materials, are harder to recycle, but innovative solutions are finding a second life for these parts: turbine blades have been successfully recycled to make concrete, surfboards, skis and even pairs of shoes. Industry is also adapting turbine design to minimise the use of non-recyclable materials.

- Solar panels are more than 95% recyclable, however Australia currently only recycles around 17% of rooftop solar panels. Industry initiatives are actively working to raise this rate, and state and Federal governments have recently agreed to progress work towards a national product stewardship scheme for solar panels, ensuring they are managed from start to end of life.

- Lithium-ion batteries are up to 95% recyclable, but we currently only recycle around 10%. By 2035, Australia could be generating 137,000 tonnes of lithium battery waste every year. A domestic recycling industry for these materials could be worth up to $3.1 billion, and will play an important part in growing Australia’s local battery manufacturing capabilities – a key priority under the Australian Government’s Future Made in Australia agenda.

Giving wind turbine blades a second life as a surfboard

The world’s first surfboards made from retired wind turbine blades were made here in Australia on the Gold Coast. In 2025, 10 prototype boards were made using decommissioned blades from a wind farm in Waubra, Victoria – made up of industrial-grade fibreglass and balsa wood. The project is being delivered in collaboration with pro surfer Josh Kerr and his surfboard brand, Draft Surf, as part of an initiative exploring innovative ways to repurpose retired wind turbine blades into new materials and products.

Pro surfer Josh Kerr. Image credit: ACCIONA Energia

What happens to the land when a project is decommissioned?

When a renewable project is decommissioned, as a general rule all the infrastructure will be removed from the site and the property will be rehabilitated or restored. The specific requirements depend on the regulations in that state or territory, and importantly, on the landholder’s agreement with the projectowner. Landholders can set out their specific expectations in their agreements, from simple restoration requirements to comprehensive rehabilitation plans with environmental monitoring. Restoring the soil is often a key step in returning land to its previous condition and ensuring it remains productive.

In most states, project owners are required to include end-of-life plans when they apply for approval to build a project. These plans are then revised over time by project owners and updated to ensure they remain appropriate, before decommissioning works begin.

RE-Alliance’s Toolkit: Refurbishment, repowering or retirement – What happens when renewables approach end of life? includes easy-to-understand information for existing and potential renewable project hosts and communities to understand the decommissioning process.

How many projects in Australia will reach retirement age in the coming decades?

Analysis by RE-Alliance shows that over the next decade, more than 1 gigawatt (GW) of wind, solar and battery storage projects around the nation will reach retirement age. That might sound like a lot, but already, more than 27 GW of large-scale wind and solar energy – and another 26 GW of rooftop solar – is powering homes and businesses across Australia. By 2045, 12.5 GW of renewables across the country could be approaching retirement age.

What has happened to existing renewable projects in Australia that have reached their end-of-life?

Australia has been installing wind and solar since the 1980s, and hydro power for more than a century. Eight renewable projects – mostly very small wind farms built to serve remote communities – have reached their end of life in Australia. Most of these have been decommissioned, but some have been refurbished or even relocated. For example, when Australia’s first large-scale single wind turbine was retired in 2014 after powering Kooragang Island in Newcastle for 17 years, it was sold and installed on a poultry farm in Northwest Tasmania.

As the tiny two-turbine wind farm on King Island in Bass Strait reached its end of life, its owner decided to refurbish, rather than decommission the infrastructure. It engaged a specialist company to restore and upgrade the turbines, and will also add new battery storage to help reduce the remote island’s reliance on diesel. The refresh is due to be complete by 2027 and will extend the wind farm’s life by at least 15 years, saving the island up to 1.8 million litres of diesel every year – saving the island on fuel costs, increasing its energy independence, and cutting climate pollution.

Are there risks to the environment and public health from decommissioning renewable projects?

Unlike fossil fuels, renewables do not produce toxic by-products or pose a contamination risk to livestock, crops or food production. Burning coal not only produces climate pollution, fuelling the climate crisis, but also emits toxic and carcinogenic substances into our air, water and land, severely affecting the health of miners, workers and surrounding communities. Historical failures in the decommissioning process in the fossil fuel sector have left local environments with significant damage and put communities at risk.

While renewables do not come with these risks, it is still important that infrastructure is removed and sites are restored or rehabilitated in ways that meet the needs of landholders and communities. Governments across Australia are strengthening requirements, and the renewables industry is showing leadership to ensure renewable infrastructure is responsibly managed at its end of life.

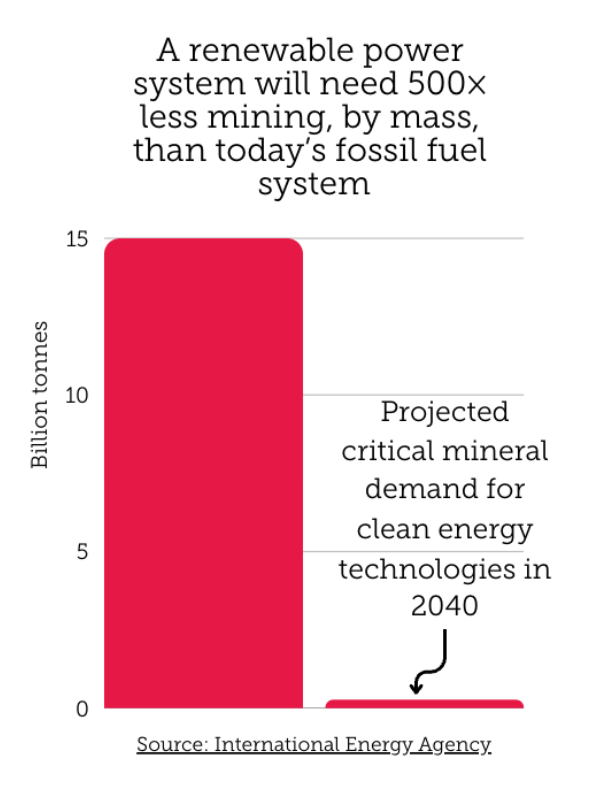

In addition, unlike fossil fuels, which cannot be re-used and must be extracted on an ongoing basis, minerals and metals from decommissioned renewable infrastructure can be reused and recycled continuously. The International Energy Agency projects that as we shift to renewables around the world, by 2040, we could be extracting around 28 million tonnes of critical minerals every year for renewable technologies. For comparison, we currently extract approximately 15 billion tonnes of coal, oil and gas every year around the world.

How can we make sure the increasing number of large-scale renewable projects are responsibly managed at their end of life?

There are already many laws, regulations and private agreement conditions designed to promote responsible retirement outcomes for landholders and communities. A lot of work is already underway to further bolster these settings to ensure renewable energy retirement is managed properly. However, there is more we can do to ensure that the renewable energy sector is sustainable throughout its lifecycle, and that communities and landholders have the information they need to have confidence in our renewable energy industry. RE-Alliance makes five key recommendations for government and industry to work together to:

- Identify opportunities for refurbishment, starting with agreeing on the circumstances in which refurbishment is appropriate and engaging with communities to increase awareness and understanding.

- Make repowering easier by investigating options to repower existing sites where appropriate, and helping project owners, investors, host landholders and communities to understand the benefits, appetite, and options for repowering.

- Improve confidence in decommissioning by developing policies to guide decommissioning that will provide clarity to landholders, ensure fair and consistent processes, and increase transparency to support landholders to make informed choices.

- Provide leadership on reuse and recycling through government coordination, investment and support for Australia’s reuse and recycling capacity.

- Enhance environmental outcomes through the development of model project conditions and best practice guidelines.

Bald Hills Wind Farm. Image credit: RE-Alliance