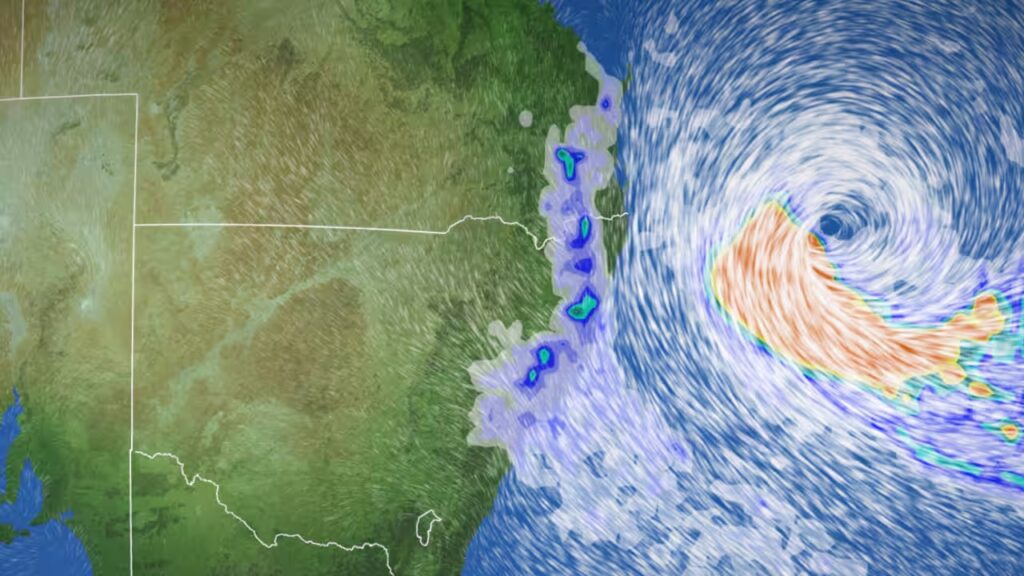

Australians are living with the everyday consequences of climate change. Heatwaves are hotter and last longer; while droughts, intense rainfall and dangerous bushfire conditions are more frequent and severe. This is already testing the limits of our capacity to cope, and we must work quickly to avoid catastrophe.

To protect Australians and do its fair share to limit dangerous climate change, we recommend Australia reduces its national greenhouse gas emissions by 75% by 2030 (on 2005 levels). What we choose to do this decade will determine the standard of living of every Australian for generations to come. With our abundant renewable energy potential, virtually no other country on Earth is better placed to achieve this. However, this will not happen if we continue to rely on existing policies and business as usual.

The solution:

From 2022, the Australian Government must begin rolling out a comprehensive series of policies and programs that reduce emissions across the entire economy: from cleaning up our transport fleet to phasing out coal and gas; upgrading the transmission network and supporting innovation for agriculture and industry. We must also better prepare for the climate impacts that are already locked in: primarily worsening extreme weather, including bushfires and droughts.

The Climate Council has set out a comprehensive list of pragmatic policies that the next Australian Government must implement. It is divided into six sections:

- How to turn Australia into a climate leader

- Preparing Australia for worsening extreme weather

- Improving existing energy policies

- Ending government support for fossil fuel expansion

- Strengthening transparency and accountability

- Reposition Australia as a trustworthy global ally

All these policies reduce greenhouse gas emissions and many will create jobs and support economic growth across regional and urban Australia. This is a clear path to economic prosperity for our country; one that will unlock investment, set up new industries and revitalise our regions. In fact, Deloitte Access Economics found that embracing a low carbon economy would add $680 billion in economic growth and 250,000 new jobs by 2070 across Australia.

This is a recipe, not a shopping list.

Government cannot pick and choose certain areas they want to focus on; rather, a whole-of-economy approach is required. These policies must be implemented in full to achieve rapid emissions reductions and help protect Australians from climate impacts. Some policy recommendations require legislation, but many do not. Some policies require new budget spending, while others will save taxpayers and government money. All these recommendations can be implemented within the next term of government.

These policies will get Australia on the right track in tackling the climate challenge head on. However, this should be treated as a sensible starting point. By continuing to strengthen our commitments and actions this decade, the federal government can turbocharge the efforts that are already underway by sub-national governments, businesses and communities all over the country. Australia can also have an outsized and positive influence on what happens next around the world. With 2030 only eight years away, there is limited time available to get this done. This is a sensible plan, but to succeed it will require a strong government that’s willing and able to act decisively in the best interests of Australians.

Make a secure, tax-deductible donation today to turn these possibilities into reality, and see it matched up to $40,000!

Click the headings below to view the full list of Climate Policies for a Sensible Government; or click the button to download the PDF version.

HOW TO TURN AUSTRALIA INTO A CLIMATE LEADER

We are on a dangerous climate trajectory, and it is in Australia’s best interests to rapidly reduce our emissions. There are tangible, immediate benefits for home owners, families, small business, workers and productivity by becoming a climate leader. To reduce emissions by 75% by 2030, a greater financial commitment for more climate solutions, new strategies and better regulations.

1. Expand the transmission network:

The Federal Government should commit to funding major transmission lines to enable Australia to achieve 100% renewable electricity. Funding should be awarded to priority projects identified in the Australian Energy Market Operator’s Integrated System Plan and to projects that will become the backbone of state renewable energy zones

2. Reform the National Construction Code:

Coordinate the approval and urgent implementation of the updates to the new National Construction Code and lock-in a 2025 review to continue improving standards. The Trajectory for Low Energy Buildings (a national plan to achieve zero energy commercial and residential buildings) should be revisited with an aim to progressing work more quickly, including mandatory energy efficiency disclosure and minimum rental standards.

3. Upgrade Australia’s ageing homes:

Roll out a national energy efficiency upgrades program. 9.5 million homes were built before energy standards came into effect. These homes are very expensive to keep warm and cool. A national efficiency upgrade program will cut power bills and emissions by replacing inefficient gas and electric appliances and improving thermal efficiency with insulation and double glazing.

4. Replace fossil fuel cars with electric vehicles:

A national strategy for electric vehicles, including cars and trucks, is needed to guide the transition to cleaner transport. This strategy should include a target to end new sales of fossil-fuel cars and rigid trucks by 2030 and committing to a fully electrified Federal Government vehicle fleet by 2026.

5. Half of all transport funding for public and active transport

Public transport, walking and cycling have a crucial role in reducing our reliance on fossil-fuel cars. A national strategy should be developed to increase public and active transport mode share. Funding should be increased for public and active transport infrastructure. At least half of all transport funding should be spent on public transport projects, with an additional $500m every year for cycling and walking infrastructure.

6. Support local manufacturing of clean infrastructure

A massive expansion of energy infrastructure is required this decade. Ensuring that this infrastructure is manufactured in Australia could support thousands of well-paid jobs across the country. Government should develop a strategy for local manufacturing of clean technologies, including wind turbines and electric buses. Government procurement rules and Australian Industry Participation Plans should be reformed to maximise the use of Australian-made products.

7. Making regional communities and public buildings clean energy hubs

Government should provide grants to community energy groups to establish community-owned clean energy hubs. There are also thousands of public buildings across Australia, including schools, that could host renewable energy and storage projects. Government should announce a comprehensive strategy to reduce emissions using public buildings. This will empower local communities, while reducing power bills and cutting emissions.

8. Invest in research and development of emerging agricultural technologies

The agricultural sector is playing an important role in land-based carbon technologies and has set strong targets to reduce emissions. Government should ensure robust standards are in place and establish partnerships across the sector to enable knowledge sharing. It should also invest in promising technological innovations that may help to reduce emissions and work with industry to commercialise them.

9. Promote clean energy exports

The Australian Government should develop comprehensive industry and trade-promotion policies that

support a massive expansion of clean energy exports – such as green steel, green aluminium, renewable

hydrogen – as well as exports of minerals such as nickel, copper, lithium and cobalt that are critical to the

development of batteries, solar panels and electric vehicles. With the right policy frameworks in place,

Australia has the potential to develop a new clean energy export mix worth $333 billion per annum –

almost triple the value of existing fossil fuel exports, according to Beyond Zero Emissions.

PREPARING AUSTRALIA FOR WORSENING EXTREME WEATHER

Australia is already feeling the brunt of climate change, with worsening bushfires, longer droughts and more flooding. To ensure we are ready for future extreme weather events, and capable of responding quickly in order to minimise impacts on communities already being felt, we need strong leadership at a federal level. This should begin by ensuring all findings of the Royal Commission into National Natural Disaster Arrangements are being implemented within the first 12 months of the next government.

1. Accept that the Federal Government has an important role to play in disaster response coordination

The Federal Government must accept that it has a fundamental role in coordination and resourcing preparation and response to extreme weather events. It should create and implement strategies to enable this.

2. Develop a National Coastal Strategy

Government should develop a National Coastal Strategy that provides a plan and framework for action on coastal inundation risks from sea level rise and extreme weather events.

3. Urgently implement all findings of the Royal Commission into National Natural Disaster Arrangements.

The Royal Commission into National Natural Disaster Arrangements made 80 recommendations. Only a handful have been fully implemented. The reason for the stalled progress is a lack of leadership and coordination. The responsible minister should direct the National Recovery and Resilience Agency (NRRA) to prioritise coordinating with State Emergency Management Ministers to implement all the recommendations as soon as reasonably practicable. The NRRA should also resume monthly reporting on progress of implementation.

4. Develop a national adaptation plan

In 2021, the 2015 National Adaptation and Resilience Strategy was updated. However, this falls short of global best practice today: national adaptation plan process (NAP). The NAP process aims to integrate climate risk into national development planning, policies and programs. Government should develop and implement a national adaptation plan process and integrate the national disaster risk management plan. Ensure federal bodies incorporate climate risks into their objectives

Government should revisit the objectives of all federal bodies tackling extreme weather, starting with the National Recovery and Resilience Agency, to ensure that they incorporate climate change physical and transition risks into their work and cover the full spectrum of climate impacts.

5. Ensure federal bodies incorporate climate risks into their objectives

Government should revisit the objectives of all federal bodies tackling extreme weather, starting with the

National Recovery and Resilience Agency, to ensure that they incorporate climate change physical and

transition risks into their work and cover the full spectrum of climate impacts.

6. More funding for disaster resilience

Disaster funding should be reformed to prioritise building resilience before a disaster strikes. Funds spent in advance of disasters have repeatedly been shown to have a better return on investment than funds spent on recovery. The principle of “betterment” – rebuilding infrastructure to a better standard than pre-disaster – should be incorporated into all recovery funding.

7. Properly resource local governments to prepare for worsening extreme weather

Local governments should be better funded to undertake essential disaster functions and prepare for extreme weather risks, including climate adaptation. At a minimum, this should include restoring the share of taxation income councils receive to at least 1% of Commonwealth taxation revenue (up from 0.5% currently).

8. Undertake an Integrated Climate and Security Risk Assessment

Climate change is a significant security risk for Australia. Government should undertake an Integrated Climate and Security Risk Assessment that includes all security sectors to ensure we can prepare for and fully understand these risks. Australia should also increase support for climate change adaptation through Australia’s development assistance program.

9. Properly model the costs of climate change impacts regularly

The Productivity Commission should conduct comprehensive modelling of the cost of current and future climate change impacts. This modelling should be conducted every three years, and include a comprehensive assessment of both chronic and acute risks from extreme weather, risks of compound events and systemic risks. This will ensure the range of impacts from climate change on our economy are fully understood.

10. Prepare critical infrastructure for extreme weather

More extreme weather is already putting our energy, water, medical and transport systems under strain. More work is needed to future-proof Australia’s critical infrastructure to ensure it can reliably power the country in the face of worsening bushfires, higher temperatures and flooding risk.

IMPROVING EXISTING ENERGY POLICIES

There are a number of existing federal policies and programs that require improvements to work effectively. These improvements should be underway within the first 12 months of the next government.

1. Reform the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (EPBC) Act

All proposals assessed under the EPBC Act should be required to disclose their emissions if they exceed a certain threshold. This emissions threshold should be consistent with the National Greenhouse and Energy Reporting Act, which sets a reporting threshold of 25kt CO2e/annum. This should include disclosure of all scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions: all emissions across the entire project lifecycle, including direct, indirect and supply chain emissions. This would also require projects to demonstrate how emissions are avoided, minimised and managed, consistent with assessment of other environmental impacts. It should be a condition of approval that emissions estimates within any proposal are not exceeded, with an accountability mechanism to ensure emissions can be independently audited.

The EPBC Act should also include an emissions trigger, enabling the decision-maker to reject a project if it would have unacceptable climate impacts. The trigger would be applied to any projects that emit more than 100kt CO2/annum. All projects should be required to demonstrate consistency with 1.5 degree and 2 degree carbon budgets for Australia.

2. Commission an independent review of the Emissions Reduction Fund

The Emissions Reduction Fund has serious integrity issues. There should be a wholesale integrity review conducted by the Productivity Commission to ensure that the standards of offsets are restored. No more auctions should be held or contracts signed until this review has been completed and all recommendations have been implemented. This review should consider all changes made to the offsets integrity standards by the CFI Amendment Act 2014. It is vital that the board of the Emissions Reduction Assurance Committee is regenerated and that its scope is limited to matters concerning the offsets integrity standards or matters directly incidental to ensuring those standards are met. The Climate Solutions Fund, which has been announced but no funding allocated, should be abandoned.

3. Support the establishment of the offshore wind industry

Review enabling legislation to ensure it is fit for purpose and continue to provide funding to help the offshore wind industry take-off.

4. Wholesale audit of the safeguard mechanism to align with net zero emissions

Government should undertake a wholesale audit of the safeguard mechanism baselines. Baselines should be set according to actual emissions, not emissions intensity. It is fundamental that the safeguard mechanism is aligned with the global goal of net zero emissions, not just the Australian goal of net zero emissions. That is, the mechanism accounts for projects that may have a low impact on Australia’s national emissions but will drive up global emissions (eg. export projects).

There should be increased oversight of individual facilities’ reported emissions and baseline setting. Baselines for all individual facilities should be reduced by 5% per year for the next three years to bring them into line with actual emissions from these facilities.

Trade exposed industries, including liquified gas export facilities, must be included within the scheme.

5. Real-time monitoring of emissions at fossil fuel facilities

All companies covered by the National Greenhouse and Energy Reporting Scheme (NGERS) should be required to disclose which of the four methodologies they use to estimate and report their emissions to the Clean Energy Regulator.

All fossil fuel facilities should be required to have some level of real-time monitoring of emissions. The Clean Energy Regulator already requires this for some facilities, such as underground coal mines. Requiring this across all fossil fuel facilities will lead to far more accurate data on greenhouse gas emissions in Australia.

6. Refresh and re-invest in the Clean Energy Finance Corporation (CEFC) and the Australian Renewable Energy Agency (ARENA)

The CEFC and ARENA have played a crucial role in supporting renewable energy and clean technologies over the last decade. Funding for both organisations should be doubled so they can continue supporting clean technologies for another decade. CEFC funding should be boosted by $10 billion and ARENA funding boosted by $2.5 billion.

The boards of the CEFC and ARENA should be reviewed and refreshed to ensure the long-term integrity and independence of both organisations.

The CEFC has been subject to repeated increases in the portfolio benchmark return levels that it is required to achieve. The portfolio benchmark return level should be restored to a weighted average of the five-year Australian Government bond rate.

ENDING GOVERNMENT SUPPORT FOR FOSSIL FUEL EXPANSION

The fossil fuel industry is by far the largest source of Australia’s emissions. Australia cannot avoid dangerous climate change if we continue to expand coal, gas or oil production. The International Energy Agency has stated that there can be no new coal, oil or gas projects if the global energy sector is to reach net zero emissions by 2050 and avoid catastrophic climate change. In 2022, Australia should end direct government support for expanding fossil fuel production, and begin developing a plan to phase down the sector to provide certainty and support to workers and communities affected.

1. No taxpayer subsidies for fossil fuels

There should be a total end to inefficient taxpayer-funded spending to fossil fuel companies. This includes funding to enable or accelerate exploration, construction of gas pipelines, power stations, coal mines and fossil-fuel derived hydrogen. No funding should be provided to federal government-owned bodies to build fossil fuel infrastructure.

2. No new taxpayer subsidies for carbon capture and storage (CCS)

No government should sink further taxpayer-funded spending into CCS projects linked to gas, coal or oil projects. CCS is a failed technology, being used as an excuse for building new fossil fuel projects releasing significant new emissions.

3. Suspend the annual offshore petroleum acreage release

Every year, the Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources release thousands of square kilometres of offshore waters to gas corporations to explore for gas. In 2021, they released another 80,000km2 to gas corporations – an area greater than Tasmania and the ACT combined. The world is shifting away from fossil fuels, gas companies are losing interest in new exploration. Government should immediately suspend the annual acreage release.

4. Introduce a moratorium on new offshore gas production

Government should implement a moratorium on the issuance of new offshore petroleum production licenses and exploration permits. This would limit the expansion of offshore gas production.

5. Reverse changes to ARENA’s mandate via regulation

ARENA’s mandate was changed via regulation in 2021 to enable the organisation to invest in non-renewable technologies, including carbon capture and storage. The changes should be reversed with a new regulation.

6. Terminate the Underwriting New Generation Investment (UNGI) Program and abandon the Grid Reliability Fund

The UNGI Program and the proposed Grid Reliability Fund were proposed to channel taxpayer dollars into gas power stations and carbon capture and storage. The UNGI Program in particular has lacked transparency from its inception. New regulations should be introduced to terminate the UNGI program and attempts to legislate the Grid Reliability Fund should be abandoned.

7. End public funding for fossil fuel infrastructure and exploration overseas

The investment mandate for Export Finance Australia should be amended to comprehensively ban investments in fossil fuel infrastructure, both in Australia and overseas.

8. Phase out the fuel tax credit scheme

New legislation should be passed to phase out the fuel tax credit scheme for mining companies by 2024. This scheme is estimated to cost the Federal Government $8 billion in 2021-22 and almost half of this went to mining companies. There are now viable, affordable and clean alternatives to diesel use to power mine operations, but the existence of this scheme is a disincentive for mines to embrace these alternatives.

9. Bilateral energy agreement reforms to include emissions reduction

Any new bilateral energy and emissions reduction agreements struck between the federal government and a state or territory government must not include any requirement to expand gas production. Existing agreements with the New South Wales and South Australian governments should be amended to remove such requirements for new gas production. Bilateral energy agreements can be amended at any time with the consent of both the federal and relevant state government. Any new agreements signed should include an emissions reduction objective to ensure new energy projects are aligned with net zero.

10. Reform the Northern Australia Infrastructure Facility (NAIF)

In 2021, a new law was passed to change the NAIF. One of the changes included in this law made it easier for the NAIF to invest in fossil fuel infrastructure. The NAIF law should be amended to explicitly ban it from investing in new fossil fuel infrastructure.

11. Proper engagement with communities at the forefront of the energy transition

Australian communities deserve to be properly consulted about new energy projects and supported as fossil fuel facilities close. Government should establish an independent body to ensure that there is an orderly transition and that communities are provided with accessible and affordable training and education services. This body should also proactively engage with communities where new energy infrastructure is located, to ensure that communities share in the benefits of renewable energy projects. This body could build off the work of the existing wind farm commissioner, with significantly greater resourcing.

STRENGTHENING TRANSPARENCY AND ACCOUNTABILITY

Good, sensible policy should be accessible to the public and there should be clear accountability for decision-making. Within its first 12 months, the next government should undertake the following actions to restore public confidence in key programs and institutions.

1. Restore the independence of the Climate Change Authority

An independent Climate Change Authority (CCA) has a vital role in providing advice to government. Government should restore the independence of, and confidence in, the CCA so that it can provide fearless reviews of government policy, as it was originally designed to do. This should include a refresh of the CCA board. The CCA should be strengthened with a significant boost in funding to enable it to carry out its tasks.

2. Increase funding to CSIRO and the Bureau of Meteorology (BOM) to restore confidence in their climate research

CSIRO has suffered from major funding cuts over the last decade, leading to many job losses. CSIRO’s annual funding should be increased, especially to enable an expansion of CSIRO’s climate research capacity. Funding to the BOM should also be increased to ensure Australians continue to have access to the best expert advice on climate, weather and natural disasters.

3. Increase accountability of the National Recovery and Resilience Agency (NRRA)

Implement all the recommendations of the Senate Finance And Public Administration Committee report ‘Lessons to be learned in relation to the preparation and planning for, response to and recovery efforts following the 2019-20 Australian bushfire season’.

Prioritise recommendation 4, specifically, “The committee recommends that the National Recovery and Resilience Agency (NRRA) develop and implement a set of operating principles which are guided by Australia’s current humanitarian and foreign aid principles. The principles should establish the role and function of the Agency and outline the ways in which the Agency will provide assistance which is trauma-informed, people-centred, and community”

And prioritise recommendations 7 through 13, that increase transparency and accountability of the $4.7 billion Emergency Response Fund, and other associated spending and funding decisions by the NRRA.

4. Establish an independent body to research gas industry emissions

Part-gas industry funded and part-CSIRO, the Gas Industry Social and Environmental Research Alliance (GISERA) is hopelessly compromised. GISERA should be abolished and replaced with a truly independent body to investigate emissions produced by gas extraction.

5. Terminate the Great Barrier Reef Foundation funding agreement

The $443 million grant provided to the Great Barrier Reef Foundation should be terminated and any unspent funds reallocated to effective government programs and bodies.

6. Replace the Technology Investment Advisory Council

The Technology Investment Advisory Council should be replaced with a panel of independent scientists, energy and technology experts to ensure government is provided with genuinely independent expert advice to guide policy-making. No members of this advisory body should have interests in the fossil fuel industry.

7. Refresh the Clean Energy Regulator

The Clean Energy Regulator is in need of a refresh of the board and senior staffing. This will ensure the organisation is well-placed to undertake the important oversight role that it is entrusted with.

REPOSITION AUSTRALIA AS A TRUSTWORTHY INTERNATIONAL ALLY

Major powers around the world are increasingly integrating climate action into their foreign policy and international diplomacy. To improve its international reputation, and better achieve its broader foreign policy objectives, Australia should use the resources of the Department o Foreign Affairs and Trade and Australia’s global diplomatic network to promote climate actio abroad. This will help to reposition Australia as a global climate leader.

1. Strengthen our Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) at COP27

The Australian Government is required to formally strengthen its Nationally Determined Contribution

(NDC) before the next United Nations climate summit in Egypt in November (COP27). A new NDC should

include an updated Long Term Strategy that sets out clear and detailed strategies, plans and policies for

Australia to achieve net-zero emissions.

2. Immediately increase Australia’s overall contribution of international climate finance to AU$3 billion over 2020-2025 and resume contributions to the Green Climate Fund

This will be a first step to ensuring that Australia is making a fair share towards the shared international goal of mobilising US$100bn per year in support for climate action in developing countries.

3. Appoint a special envoy for climate change

Establish a position of Climate Change Ambassador within the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade,

separate from the existing Ambassador for the Environment. This role should be tasked with promoting

global climate action, working with key allies and partners to step up climate ambition, and promoting

Australia’s clean energy exports.

4. Bid to host the next global climate talks

The Australian Government should bid to host the annual Conference of Parties to the United Nations

Framework Convention on Climate Change as soon as possible. Hosting the United Nations (UN) climate

talks would be a chance to showcase Australia’s role in the global energy transition and would strengthen

Australia’s reputation as a nation committed to the rules-based international order. Australia should seek to

co-host a UN climate summit with Pacific island nations.

5. Work closely with Pacific island countries to promote climate action

Work toward a regional declaration at the 2022 Pacific Islands Forum calling for all countries to set more

ambitious 2030 emissions reduction targets before COP27. Australia should also establish an annual

climate dialogue with Pacific island nations.

6. Host an Indo-Pacific clean energy forum

Host an international forum (with key partner nations and the International Energy Agency) on clean

energy supply chains in the Indo-Pacific, to promote Australia’s ability to support countries in our region

as they transition to net-zero emissions economies.

7. Help Indonesia accelerate its move away from coal

Work with other developed economies in the lead up to the G20 summit in Bali in October to design

a financial package that helps Indonesia accelerate its transition away from coal-fired power stations.

8. Work closely with key security allies on climate action

Formally declare climate action a key plank of security cooperation with key allies, such as the United

States, and work with allies to accelerate the shift to clean energy in the Indo-Pacific.