With the launch of the Climate Council’s Gas Exploration Map, this article provides an overview of where Australia’s existing and proposed gas projects are located.

To avoid dangerous climate change there can be no new fossil fuel infrastructure. This is the consensus from climate scientists, the European Union, the United Nations and even the traditionally conservative International Energy Agency.

Gas is a polluting source of energy that is bad news on many fronts: it’s driving climate change, worsening asthma in children, driving up power bills and is increasingly unnecessary as Australia transitions to cleaner, cheaper sources of power (*ahem* renewables). Induction cooktops and electric heating in the home, renewable hydrogen for industry, and batteries and pumped hydro in the electricity sector have all combined to mean that gas is increasingly obsolete.

But it seems someone forgot to tell Australia’s gas corporations and the Federal Government.

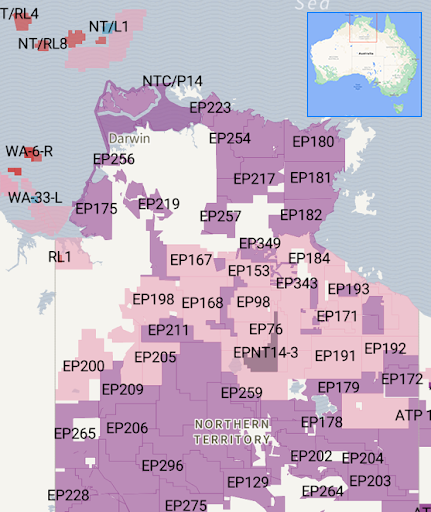

Few Australians are aware of just how much of Australia’s pristine land and waterways is under threat from gas companies. To comprehend the immensity of this scale, a country-wide map is required, one most would find absolutely shocking. In fact, a disturbing 28% of Australia’s land mass is currently subject to gas exploration or applications from gas companies. This includes a whopping 70% of the Northern Territory, 59% of South Australia, 14% of Western Australia and 13% of Queensland.

Across Australia, new gas projects are being proposed left, right and centre. From Woodside and BHP’s gigantic Scarborough gas project in north-west Western Australia to Santos’ Narrabri project in northern New South Wales, it seems nowhere is safe from the gas industry.

While Victoria has permanently banned unconventional gas extraction* and Tasmania has a moratorium* on fracking* until 2025, much of the country remains at risk from new gas projects. This is especially concerning as a big proportion of Australia’s proposed projects are in unconventional gas fields, which are generally more dangerous to human health and the local environment compared to older conventional fields*.

There are deeper, cultural costs, too. Many of the areas where gas is being explored are in culturally and environmentally significant areas to Australia’s First Nations peoples. Gas exploration threatens First Nations people’s connection to country in many ways, risking the land, water and cultures that they have relied on for countless generations.

To rub salt into the wound, the Federal Government is opening up over 80,000 km2 of offshore waters to gas companies—an area larger than Tasmania and the ACT combined! At the same time they are providing taxpayer-funded handouts to build a gas power station and supporting the development of new gas fields.

For any unfamiliar words, scroll down to the glossary at the bottom of this article.

Let’s start with a look around the country at existing projects.

Current major gas developments

These areas contain established gas projects where gas extraction has been underway for a number of years.

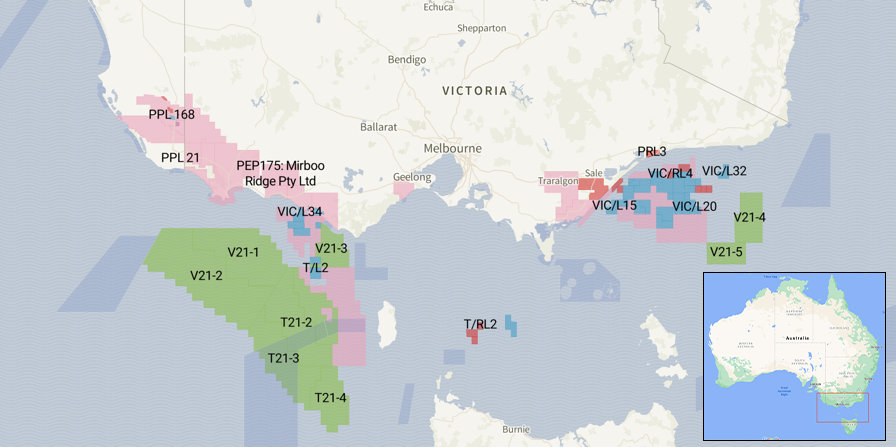

Bass Strait, Victoria and Tasmania

For the last few decades, Bass Strait has been supplying most of eastern Australia’s domestic gas. For decades, these conventional gas fields have been the primary suppliers of Victoria and New South Wales’ gas needs but they are starting to run out of gas. Although there is ongoing exploration, production is expected to significantly decline over the next decade. This presents a great opportunity to begin reducing demand for gas and continue the process of transitioning households and businesses to all-electric appliances.

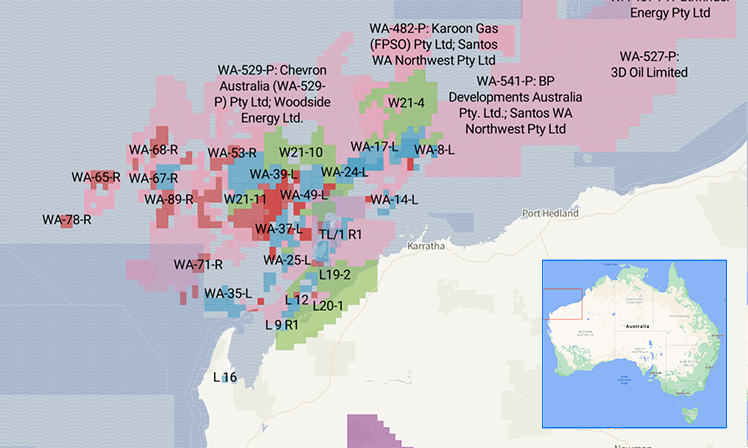

Offshore North-West shelf, Western Australia

Western Australia is the country’s largest producer of gas, accounting for about 60% of Australia’s gas production. The offshore territory around Karratha in the north-west contains a range of conventional gas fields, some of which have been operating for decades, to feed the state’s massive North-West Shelf liquified gas export terminal* (which converts gas into a liquid form, allowing it to be shipped to countries overseas). Significant gas reserves remain in the region, which gas companies are planning to open up (see next section). Although gas production has occurred here for decades, production has almost doubled since the mid-2010s to supply three new liquified gas export terminals (Gorgon, Wheatstone, Pluto). A fourth terminal, the Prelude floating gas terminal, opened in 2019 and is also located around 500 km north of Broome (although it is serviced from Darwin). This has contributed to a substantial increase in Western Australia’s emissions over the last decade.

Did you know…

Western Australia has more liquified gas export terminals than any other state

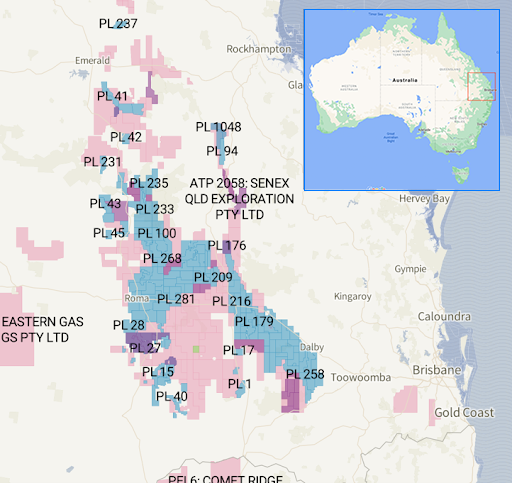

The Darling Downs, Southern Queensland

The Surat Basin is a massive unconventional gas field located in the Darling Downs region of southern Queensland inland from Brisbane, the Sunshine Coast and Bundaberg. This unconventional gas field contains coal seam gas* which is often extracted by fracking. Most of the new production in this field has been developed over the last decade to supply gas to three new liquified gas terminals for shipping overseas (Curtis, Gladstone, Australia Pacific). These three terminals sit next door to one another on Curtis Island, next to Gladstone and all opened between 2014 and 2016. The development of the Surat Basin has been a core driver of Australia’s rising emissions over the last decade and a key driver of rising energy prices on the east coast.

Offshore Northern Territory

The Northern Territory currently produces a small amount of gas in the Amadeus Basin near Alice Springs but most of the Territory’s gas is currently produced offshore. The major field is the Bayu-Undan gas project in Timor-Leste’s waters, which supplies gas to Santos’ Darwin liquified gas export terminal. This gas project is reaching the end of its life and Santos is currently looking for a new source of gas (see next section). The Darwin gas export terminal opened in 2006 and was joined by INPEX’s Ichthys liquified gas terminal in 2018, which is supplied by gas located in Western Australia’s offshore waters. Darwin also services Shell’s Prelude floating gas export terminal.

The Cooper Basin (South Australia and Queensland)

The Cooper Basin is a largely conventional gas field based in north-east South Australia and south-west Queensland. Like the Bass Strait, this region has been a significant supplier of gas for domestic use for decades but it has passed its peak. Although exploration continues for new sources of gas in the area, particularly unconventional gas, production is not expected to expand significantly.

Major proposed gas developments

These are the main areas where gas projects have been proposed around Australia. To limit the harm of climate change, none of these projects can go ahead.

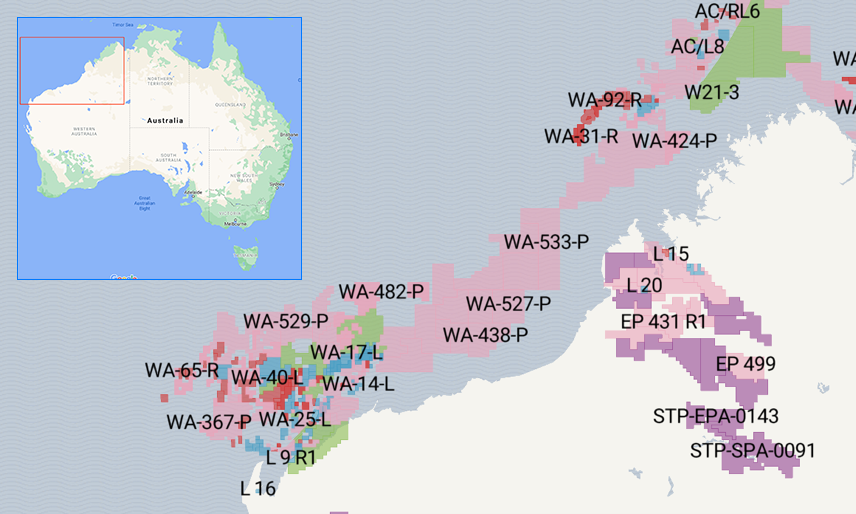

North-west Western Australia (offshore)

Almost the entire offshore area along Western Australia’s north-west coast, from Karratha up to the Northern Territory border is currently being explored for gas. This region contains a massive quantity of conventional gas and if burnt could be catastrophic for our attempts to limit global temperature rise.

The most concerning proposed project is Woodside and BHP’s massively polluting Scarborough and Pluto expansion project, which would be one of the most polluting fossil fuel projects ever built in Australia if it goes ahead.

There are many other highly polluting proposed projects in this region. These include:

- Woodside’s Browse project

- Chevron and Woodside’s Clio-Acme project

- Shell’s Crux project

- PTEEP Australasia’s Cash Maple project, and

- Western Gas’ Equus project

Each one of these projects would lead to a colossal release of additional greenhouse gas emissions, which, in turn, would translate to increasing temperatures and greater harms to lives, livelihoods and the places we cherish.

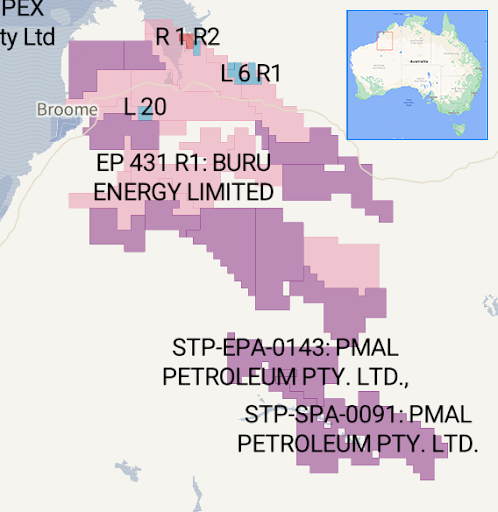

The Kimberley, Western Australia

A number of gas companies are exploring for onshore unconventional shale gas* near Broome in the Kimberley of north-west WA. This culturally and ecologically sensitive area is under threat from fracking by a number of gas companies, including Buru Energy, Origin Energy, Theia Energy and Black Mountain Oil and Gas (Bennett Resources). This area contains significant gas reserves, which will drive up emissions if burnt. The widespread use of fracking, which is required to access shale gas, risks significant impact on local communities and the local environment. Gas exploration is already having a massive impact on areas that are culturally and ecologically significant to Australia’s First Nations peoples throughout the Kimberley. One gas company has cleared 14,000km in a straight line through the Kimberley bush—the same distance from Perth to London.

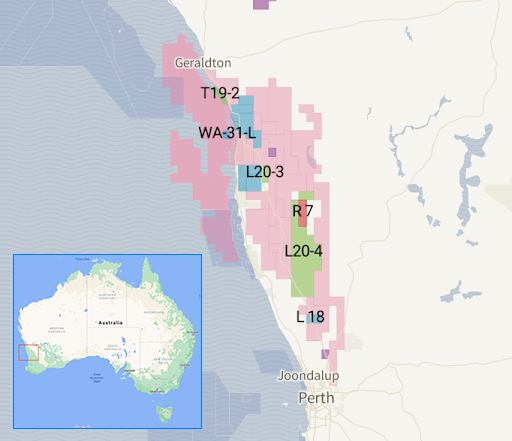

Geraldton and the Perth Basin, Western Australia

The offshore and onshore region stretching north of Perth to the regional city of Geraldton is being heavily explored for gas. Two of the largest projects are the Waitsia project (Beach Energy and Mitsui) and the West Erregulla project (Strike Energy and Warrego Energy). This area contains prime agricultural land which is at significant risk from unconventional gas extraction, especially fracking. Although fracking has been banned by the Western Australian Government in small parts of this region, it is still allowed in much of this area.

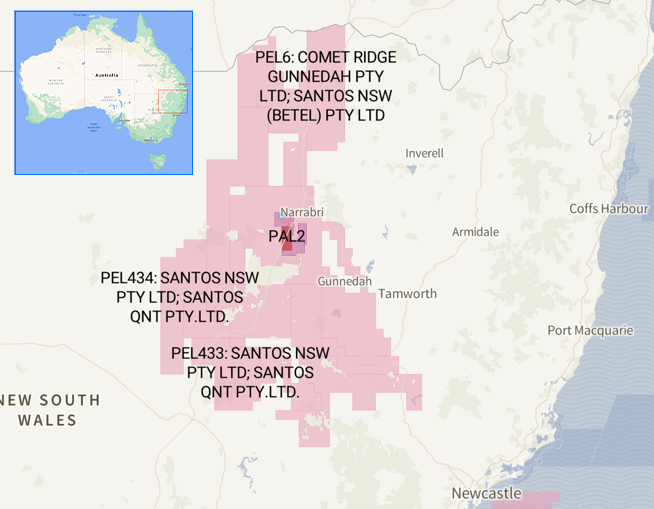

Northern New South Wales

The agricultural region of northern New South Wales, inland from Port Macquarie and Coffs Harbour, contains coal seam gas*. The main proposed project in the area is Santos’ Narrabri project. There is also a large number of expired exploration permits that cover a significant section of prime agricultural land in the region all the way up to the Queensland border. The NSW Government has recently committed to prohibiting gas exploration in eight of these twelve expired permits.

The New South Wales Government has not banned fracking.

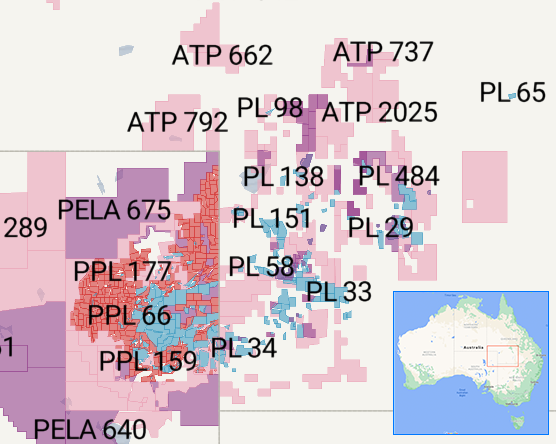

Offshore Northern Territory and the Beetaloo Basin

The Northern Territory appears almost entirely covered by exploration permits and applications from gas companies. Much of the NT’s gas lies within the Beetaloo Basin, which covers a vast region of central NT. This region contains unconventional tight gas* that can only be accessed by fracking.

There is a huge quantity of highly polluting gas in the Northern Territory that must stay in the ground if we are to avoid catastrophic climate change. Using fracking to extract this gas could cause irreversible impacts on local communities, groundwater and the environment. Traditional Owners fear the negative consequences of fracking on sacred sites and waterways.

There are also two large gas projects proposed in the NT’s offshore waters. This includes Santos’ Barossa project, which would be one of the most emission intensive gas developments in Australia. This project is intended to continue supplying the Darwin liquified gas export terminal, which will soon run out of gas. Woodside is also planning the Greater Sunrise gas project with Timor-Leste’s national oil company Timor GAP. This project is located across both Australia and Timor-Leste’s national waters.

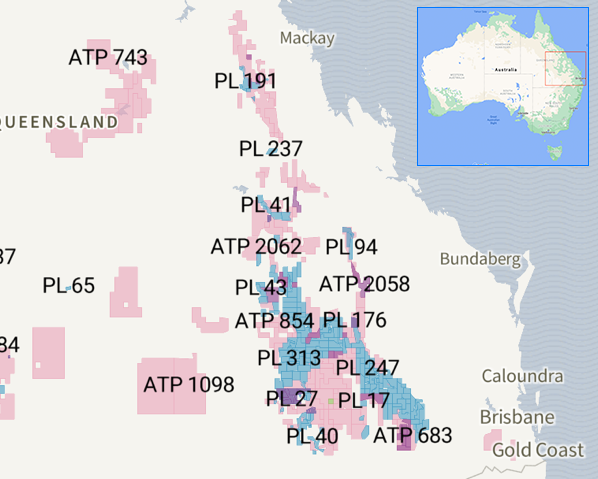

Central Queensland

Almost all of Australia’s unconventional coal seam gas is currently produced in Queensland and there are a number of new coal seam gas projects proposed in the Surat Basin in the Darling Downs, the Bowen Basin (inland of Bundaberg and Mackay) and the Galilee Basin (to the far west of Mackay).

In the Bowen Basin, one proposed project is Arrow Energy’s Bowen gas project and another is the Mahalo project (Santos, Comet Ridge and APLNG). In the Galilee Basin, Galilee Energy has proposed the Glenaras project.

However, most of Queensland’s proposed gas projects are located in the existing Surat Basin. Many of these projects are backed by Arrow Energy, while the Roma North project is backed by Senex and the Goog-a-binge project by Shell.

This list is not exhaustive. For more information on gas and climate change, check out our resources below.

Reports

Explainers

- Why is gas bad for climate change and energy prices?

- What is the National Gas Infrastructure Plan? And do we need new gas pipelines?

- What is hydrogen?

- What is carbon capture and storage?

- Biogas, green gas and renewable gas: when good ideas are used to justify terrible ones

Glossary

Conventional gas – Conventional gas is trapped in naturally porous reservoir formations that are capped with rock. When a well is drilled, gas flows to the surface without the need for additional, and often riskier, measures. Jump back to article.

Unconventional gas – Unconventional gas is found in more complex geological formations that limit the ability of gas to be extracted. The term ‘unconventional’ means that extra steps must be taken to extract the gas from underground. This includes fracking, but covers other measures as well including horizontal drilling and dewatering. Not all unconventional gas requires fracking, but this process is often required as well. Three types of unconventional gas are extracted in Australia: coal seam gas, shale gas and tight gas. Jump back to article.

Coal seam gas – Coal seam gas holds methane absorbed on underground coal seams. This gas is often held in place by rock and ancient groundwater (‘fossil water’). This water must be removed to access the gas, in a process known as ‘de-watering’. As a result, CSG poses significant risks for local users of groundwater, including farmers and sensitive environments downstream, if the water is extracted from the aquifers that farmers use or if produced water is not managed appropriately. CSG extraction often uses fracking to increase the supply of gas (see below), but this is not always required. Jump back to article.

Shale gas – Shale gas holds methane in clay-rich, layered rock formations known as shales. Within these shales, the gas is contained in small pores that do not allow the gas to flow freely. Fracking is almost always required to access shale gas in economically viable quantities. Jump back to article.

Tight gas – Tight gas is similar to shale gas in most ways, but the methane is found in sandstone or limestone rather than shales. As with shale gas, tight gas extraction almost always requires fracking. Today, there is very little tight gas production in Australia, but several potential reserves have been identified. Jump back to article.

Fracking – Fracking (also known as hydraulic fracturing) is one of the most environmentally damaging ways to extract fossil fuels. It involves forcing massive quantities of sand-bearing water, loaded with chemicals, deep underground. The pressure behind the fluid mix creates new cracks in the rock, which allow the gas to flow more freely to the well.

Fracking uses many dangerous chemicals. These can contaminate local land and water supplies. The identities of the specific chemicals used in a fracking operation are usually kept secret from the communities they affect, and, if something goes wrong, can cause catastrophic damage to local agriculture, bushland and waterways. Potential health problems caused by fracking chemicals include cancer, nervous system damage and respiratory problems. Fracking is a catastrophic risk. Jump back to article.

Liquified gas export terminal – Also known as an LNG facility, liquified gas export terminals convert gas into a liquid form, allowing it to be shipped and exported overseas. Gas is transferred to these terminals via pipeline and large amounts of energy are used to cool the gas to -160 degrees, converting into a liquid. Tankers then transport this gas to other countries where import terminals then convert the liquid gas back into a gaseous form to be burnt for power. This process wastes a lot of energy. The gas export industry wastes more gas processing its product for export than is used by Australia’s entire manufacturing sector. The consumption of this gas at this scale is also highly polluting. Liquified gas export terminals are currently in Western Australia, Queensland and the Northern Territory. Jump back to article.

Moratorium – A moratorium is a temporary government ban on an activity. In Tasmania, the state government has introduced a moratorium on fracking until 2025. Both Western Australia and the Northern Territory in the past have had moratoriums on fracking but these were lifted in recent years. Jump back to article.