Bushfires are becoming more extreme and harder to control.

Climate pollution from burning coal, oil and gas is turbocharging Australia’s bushfire risk. Climate change is making hot days hotter, droughts more severe and heatwaves longer and more frequent – and far more dangerous bushfire weather across the country.

Fire seasons across large parts of Australia are now longer, more volatile and increasingly overlapping. This means there are fewer and shrinking windows in which to prepare for fires, by doing things like hazard reduction burning. Also, fires are harder to control once they take off.

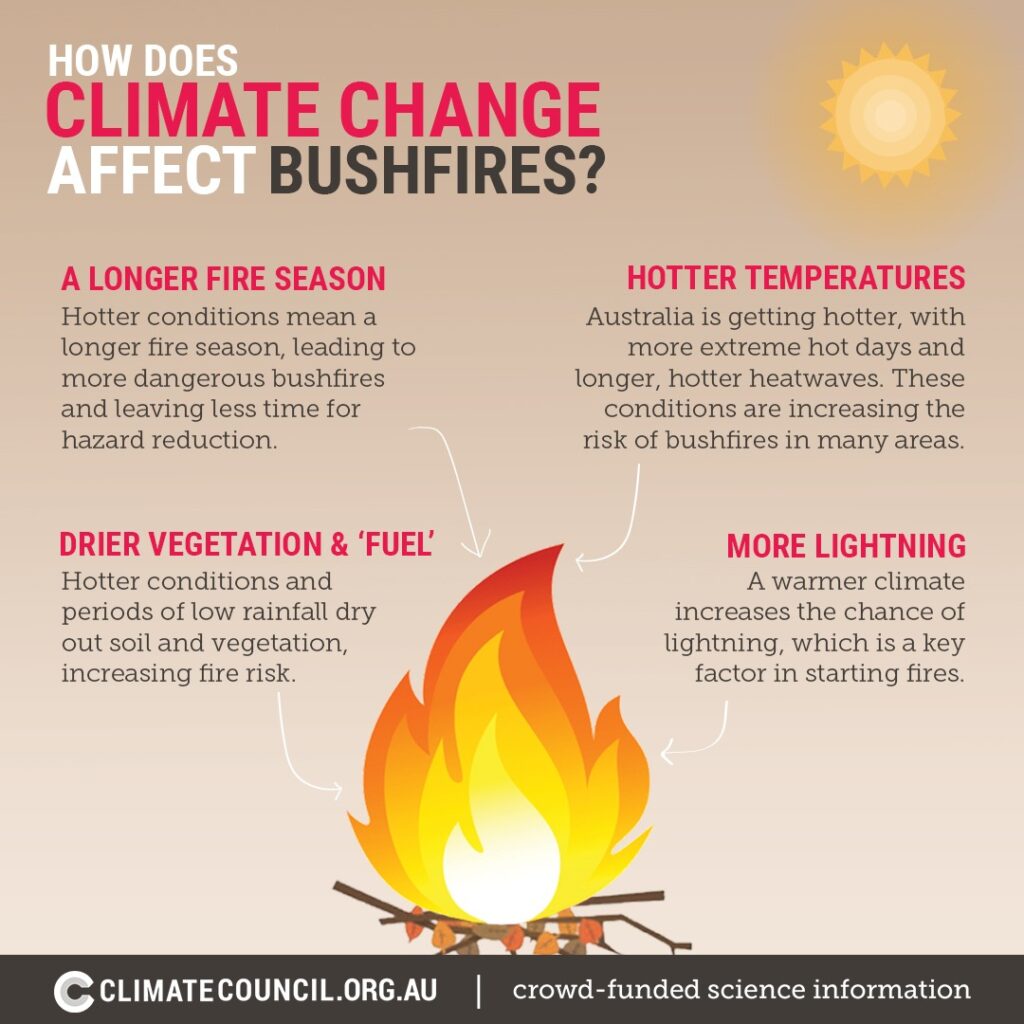

How is climate change influencing bushfires?

A fire needs to be started (ignition), it needs something to burn (fuel), and it needs conditions that are conducive to its spread (i.e dry, windy weather). Climate change, primarily driven by the burning of fossil fuels – coal, oil and gas – can affect all of these factors in both straightforward and more complex ways.

Australia, on average, has warmed by 1.51°C ± 0.23 °C since national records began in 1910, with most warming occurring since 1950. Nine of Australia’s top 10 warmest years on record have occurred since 2005. At the same time, a decline in cool season rainfall in southeast Australia is contributing to an increased likelihood of more dangerous bushfires. Extreme fire weather has increased over the p last 30 years in south and east Australia. The most extreme 10% of fire weather days has increased in recent decades across many regions of Australia, especially in southern and eastern Australia.

Hot days and heatwaves

The most direct link between bushfires and climate change comes from the long-term trend towards a hotter climate. Climate change is now making hot days hotter, and heatwaves longer and more frequent.

In Australia, the annual number of hot days (above 35°C) and very hot days (above 40°C) has also increased strongly over most areas since 1950. Heatwaves are also lasting longer, reaching higher maximum temperatures and occurring more frequently over many regions of Australia.

Extreme heat conditions preceded the Black Saturday bushfire in 2009 – Australia’s most deadly bushfire. In late January, Victoria experienced one of its most severe heatwaves, with Melbourne exceeding 43°C for three consecutive days; the first time on record. The extreme heat dried out flammable vegetation across the state, setting the stage for catastrophic fire conditions. When the Black Saturday fires took off on the 7th of February, temperatures climbed into the mid-40s and Melbourne had its hottest day on record at the time.

Low Rainfall

Declining cool season rainfall has a significant impact on increasing bushfire risk. Since the mid-1990s, southeast Australia has experienced a 15% decline in late autumn and early winter rainfall and a 25% decline in average rainfall in April and May. Climate change is influencing this drying trend.

In the lead-up to January 2003, the ACT endured one of the worst droughts in recorded history. Rainfall was at record lows — just 40mm compared with an average of 150mm. On 18 January Canberra experienced the most destructive bushfires in its history.

From 2017 to 2019 southeast Australia experienced its driest three-year period on record. The Tinderbox Drought was severe and pushed rural towns to the brink of running dry. It set the stage for the bone dry conditions that contributed to the Black Summer bushfires of 2019/2020, which burned more than 24 million hectares of land and led to the deaths of 33 people and almost 450 due to smoke inhalation.

Lengthening seasons

Since the 1970s, there has been an increase in extreme fire weather and a lengthening of the fire season across large parts of Australia, particularly in southern and eastern regions, due to increases in extreme hot days and drying.

The lengthening fire season means that opportunities for fuel reduction burning are decreasing, and it is putting higher demand on our firefighting services.

Strong winds

Many of Australia’s most destructive bushfires have been fanned by strong winds that have driven explosive fire spread. Strong winds were a factor in the spread of the destructive Cudlee Creek and Gospers Mountain fires during the 2019/20 Black Summer.

More recent fires on Tasmania’s east coast in late 2025 that claimed 19 homes at Dolphin Sands were also driven by strong gusty winds, and occurred despite recent wet weather. Strong winds can also limit the effectiveness of aerial firefighting. Strong gusty winds can send the water or fire retardant dropped from aircraft far from the fire ground. In some instances winds can be so strong that it is unsafe to fly, limiting firefighting efforts to an on-the-ground response.

More intense fires

Fires are now so intense they create their own wild thunderstorms, hurricane strength winds and lightning. Pyrocumulonimbus (pyroCb) events occur when bushfires couple with the upper atmosphere, generating explosive thunderstorms that can include strong downdrafts, lightning and even black hail.

These events are more likely to occur when atmospheric instability is high, combined with dangerous near-surface conditions (e.g. low humidity, strong winds and high temperatures). They happen when large fires generate intense heat and convection columns that reach into the stratosphere, forming cumulonimbus (storm) clouds, but with very little moisture and therefore generating little, if any, rain.

A pyroCb can cause already intense fires to expand and behave explosively, with storm force winds coming from different directions, lightning that causes new fires up to 100km away, and downdrafts that can damage buildings, fire trucks, and push down trees.

From 1979 to 2016 south-eastern Australia has experienced an increase in conditions conducive to the formation of fire-generated thunderstorms. Climate change will continue to amplify these conditions and could lead to more fire-generated extreme weather over longer fire seasons.

Learn more in our report, When Cities Burn: Could the LA fires happen here?.

What is expected in the future?

Unfortunately, fire weather across Australia will get worse. Climate change is driving hotter temperatures alongside drier conditions across southern Australia – increasing the risk of bushfires. Southern and eastern parts of the country will see more days of dangerous fire weather, longer fire seasons and the potential for more megafires.

The latest research on the fire risks Australians face

The fires that ripped through the neighbourhoods of Los Angeles in the United States, in the middle of winter, shocked the world. They left many people asking: could this happen here in Australia?

Our latest Climate Council and Emergency Leaders for Climate Action report, When Cities Burn: Could the LA fires happen here?, finds:

1. Climate pollution from the burning of coal, oil and gas shaped the dangerous and extreme weather conditions that drove these fires.

Record dryness; non-arrival of the typical annual wet season; and hurricane-like winds gusting up to 160 kmh.

2. The outskirts of many Australian cities share the dangerous characteristics that made the LA fires so destructive

Sydney, Melbourne, Canberra, Adelaide, Perth and Hobart are all vulnerable.

Many of our own bushfires have exhibited the same, unstoppable behaviour: During Black Saturday 2009 in Victoria, the fire danger index exceeded 200 (with 100 the upper limit of recognised fire danger rating up until 2009).

Fire-generated thunderstorms, or pyroconvective events, were relatively rare with 60 such events recorded in Australia in the 40 years up to 2018. During Black Summer, at least 45 fire-generated thunderstorms were recorded.

While we associate our most destructive fires with extreme heat, bushfires only need a combination of dryness and strong wind to grow and spread rapidly.

3. Just like in LA, more people than ever are living in harm’s way on the fast-growing urban fringes of Australian cities

There has been a 65.5% average jump since 2001 across Melbourne, Perth, Sydney, Hobart, Canberra, Brisbane and Adelaide with 6.9 million people are now living on the outskirts of these cities.

Had the Black Summer bushfires directly impacted the edges of our cities or major regional centres, such as Sydney, Newcastle, Wollongong, the NSW Central Coast, the Dandenong ranges, the Adelaide Hills, the Perth Hills or Hobart, then property losses on the scale of LA could have occurred.

Up to 90% of Australian homes in high-risk fire zones were also built before modern bushfire standards existed — making ignition due to ember attack and house-to-house fire spread far more likely.

4. This is costing all of us – today.

Since 2020, insurance premiums have increased by 78% to 138% for homes in bushfire-prone Local Government Areas within Sydney, Melbourne and Perth. Even those who don’t live in the path of fires or floods, are paying for more insurance today, because climate-fuelled weather everywhere means higher insurance for everyone.

What can be done?

As a priority, all governments must:

- Cut climate pollution from coal, oil and gas more swiftly and deeply if we’re to avoid even worse.

- Invest heavily in disaster preparation and community resilience at all levels of government so we’re as prepared as possible for the worsening fire risks we already face.

- As a priority, increase emergency service and land management capacity at the urban fringe of our cities and major regional centres so growing populations are better protected for what’s to come.

We’ve created a digital resource to help you share the When Cities Burn: Could the Los Angeles Fires Happen Here? report with your local representatives, and ask them to support stronger national action to cut climate pollution this term. Act now! Raise your concerns about climate-fuelled bushfire risk today.