By Stephen Sutton PhD, Emergency Leaders for Climate Action member and former Chief Fire Control Officer for the Northern Territory. Published in The Canberra Times here.

2011 was the worst year of my life. I was living in the Northern Territory, working as Chief Fire Control Officer and that year, 67% of the Territory burnt. A death in my family cast a pall over my personal life, but the horrendous fire season turned work from ‘challenging but rewarding’ to ‘impossibly challenging and dangerous’.

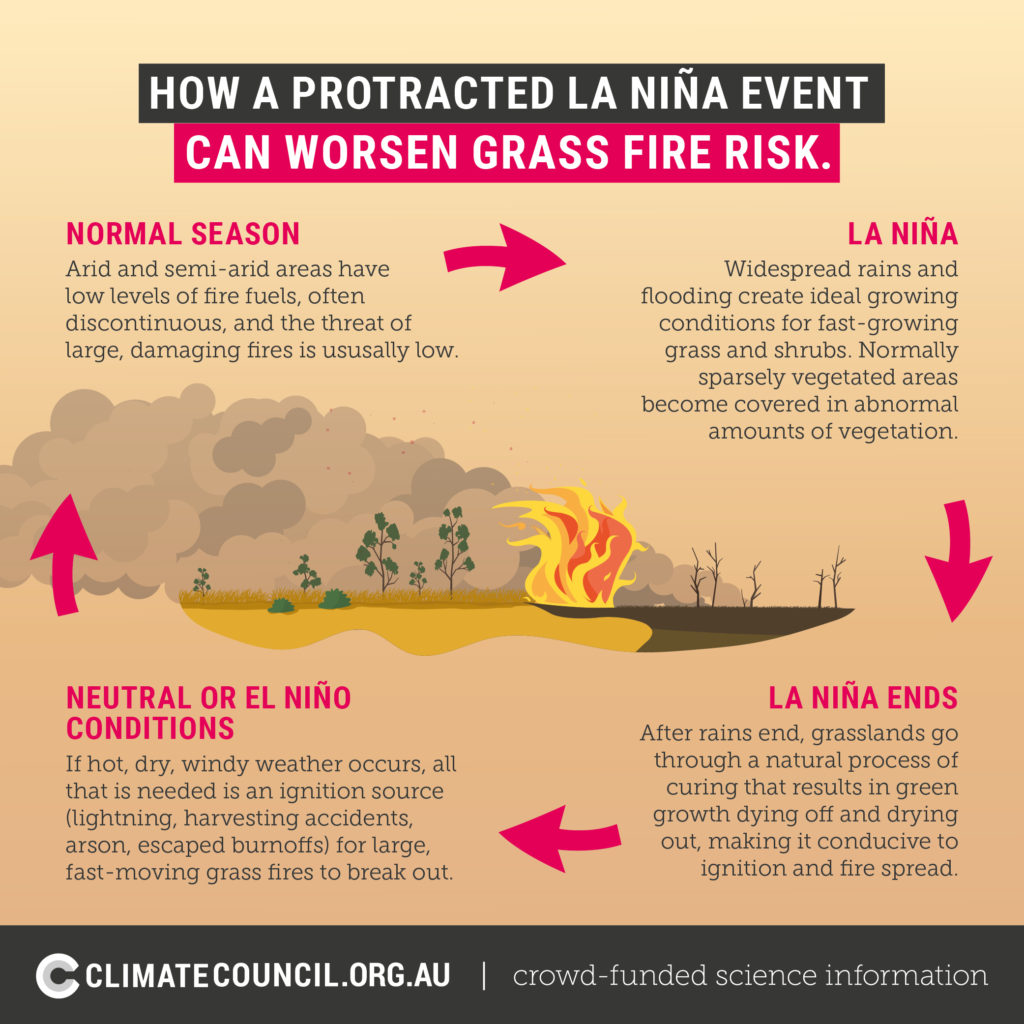

While much of the Northern Territory is desert or semi-desert, it periodically receives huge rainfall, and this encourages intense vegetation growth. Much of this is grass and scrub which grow rapidly, creating a blanket that stretches out to the horizon. As the weather clears, and temperatures climb back to the 40’s, the plants dry out and create a seamless cover of bushfire fuel.

This pattern, supercharged by climate change, repeats every ten to twelve years with devastating impacts. 2011 was one of those years and I fear we are heading into another. As I write, the first of the fires have started to rage in the Northern Territory, and the peak council for Australian Fire and Emergency Services has indicated that as much as 80% of the region may burn this summer. Fire seasons are getting worse, and climate change is the culprit.

Read our latest report on Australia’s bushfire preparedness here.

In 2011, fire preparation practices were manifestly inadequate, constrained by budget as well as weather. The window for fire management (the period when the weather is suitable for fuel reduction burning) had become narrower.

Even back then, climate change meant that the small number of people dedicated to reducing fire risk had much less time to do it. To make matters worse, introduced grass species, gamba in the north and buffel in the south dramatically increased fuel density. Fires burned higher and hotter.

When the fires started, it was all hands to the pumps. Intense efforts were made to protect infrastructure and homes, but a huge amount of damage occurred. Fires wiped out habitat critical for saving the endangered desert rock rat and the mala from extinction. Time and again, people just managed to escape, their lives forever changed by other losses.

I vividly remember the afternoon we dispatched one of our most experienced bushfire managers to try to hold a fire that was encroaching on Alice Springs. A Warramunga man, he got off the plane from Darwin and went straight to the fire front. He quickly organised a massive back burn along bush tracks west of the town. This took immense confidence and courage. By about 9:30 that night I started to get phone calls from fearful residents who saw the towering walls of flame. What they saw was, in fact, the success of the backburn; it had joined up with the wildfire, leaving a trail devoid of fuel that saved their homes.

Lives were undoubtedly saved by the decisions made by the likes of my colleague in 2011. But today, the only decision that can save us from a future marred by much worse fire seasons, is the decision to leave fossil fuels in the ground.

Climate change continues to make fire management ever more difficult. Twelve years on and we know much more about the driving forces behind worsening extreme weather, but we’re not doing nearly enough about it. Just months ago, the Northern Territory Government announced that it would go ahead with a fracking project in the Beetaloo Basin, projected to emit the equivalent of more than three times Australia’s annual domestic emissions over the next two decades. We’re adding fuel to the fire by approving new fossil projects like this, heating up Australia and the world, priming the planet to burn.

Just like it was twelve years ago, the centre of Australia is covered with vegetation. Three La Niña years are likely to be followed by an El Niño. The weather is more extreme; already, the hottest days are hotter and there are more of them. We know to expect warm, windy weather just when the vegetation is at its driest. The fire conditions have become so bad that our official fire danger rating will be pushed into the category of ‘catastrophic’.

We have to drastically and urgently reduce our emissions if we want to give our country a fighting chance against fire seasons to come. If we don’t, I fear for communities in the Northern Territory and across Australia, who may well experience the worst year of their lives, just as I did in 2011.