This month we’ll be bringing you updates from the annual Conference of the Parties in Katowice, Poland courtesy of our climate councillor, Professor Hilary Bambrick.

Update 7: Are we there yet? March for climate action in Katowice

Sunday, Dec 9, 2018

I attended the huge march for climate action that took place on Saturday in Katowice, to demand action from country negotiators at COP24.

Reflecting the growing climate movement around the world, there was a strong youth presence at the march, with demands for urgent action from those with the power to protect younger people and future generations. Many international observers from NGOs who are participants at COP24 attended the march, along with environmental activists from around the world. The march was also extremely well attended by locals who want their country to give up its coal dependence for the sake of the planet and its people.

Protesters at the COP24 conference in Katowice, Poland. Image- Prof. Hilary Bambrick

Protesters at the COP24 conference in Katowice, Poland. Image- Prof. Hilary Bambrick

March organisers called on COP24 negotiators to stop arguing over definitions, to stop avoiding responsibility and start making decisions that would mean countries get on with the job of mitigation through deep and meaningful emissions cuts. The key message from demonstrators is that we need to quit coal, oil and gas fast, and support the switch to renewable energy.

Australians at the COP24 protest in Katowice, Poland. Image – Linda Selvey

Australians at the COP24 protest in Katowice, Poland. Image – Linda Selvey

The energy in the crowd was immense and positive, with chants, music, and dancing along with speeches. All of this set against the very real sense that this is just about the last chance to set the world on the right path.

And that’s all from me direct from COP24 in Katowice. As the negotiations head into their second week, where ministers join the talks and decisions start getting bedded down, you can stay in touch with what is happening on the inside through the daily updates held by Climate Tracker, and also with the headlines from COP24live.

Update 6: Human rights thrown out of the rulebook

Saturday, Dec 8, 2018

While country delegates try to nut out the rulebook for how the Paris Agreement is to be implemented and how countries will be held to account, various countries and interest groups are trying to get certain items included or excluded.

The big news of today is that Human Rights, Gender Responsiveness and Indigenous People’s Rights were all cut from the current rulebook text, and instead will only get a mention in the preamble.

This deals a massive blow to groups who have been working hard to get rights and protections for vulnerable groups embedded in implementation plans and accountability, so that progress on protection can be officially audited.

Why does embedding the protection of rights in the text of the rulebook matter? While everyone is affected by climate change, some groups are much more at the mercy of changing climate than others, because of poverty or other marginalisation. Holding countries to account for the right to health, for example, means taking specific action to ensure that the needs of the most vulnerable are attended to.

Dr. Diarmid Campbell, World Health Organization discusses the COP24 special report on health and climate change

Even on the seemingly least contentious issues, it’s hard to get agreement because different countries have different agendas. Some countries participating in the COP negotiations are seen by others as universal disrupters, digging in their heels in every negotiation in an apparent attempt to derail the talks. Australia sees itself as occupying the ‘practical middle ground’ in negotiating solutions.

Health is fairly well represented at this COP, and has been given a louder voice than at previous meetings. Organisations include the Global Climate and Health Alliance (GCHA), Australia’s Climate and Health Alliance (CAHA), the Royal Australasian College of Physicians, Healthcare without Harm, and the World Health Organisation. These groups have been building connections all week.

In other news, today the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade held its first and possibly only briefing meeting with all the COP attendees from Australia. These include NGO groups, such as the Climate and Health Alliance who I am representing, the Australian Youth Climate Coalition, the Royal Australasian College of Physicians, as well as Australian oil and gas industry representatives including from Woodside. This briefing provided an opportunity for the Australian delegation to share progress on negotiations, and for attendees to ask questions of the negotiators.

Update 5: Taking stock of global emissions

Friday, Dec 7, 2018

Global emissions in 2018 have increased to their highest ever level, according to a new report just released by the Global Carbon Project and launched in Katowice, with emissions still growing in a number of countries. Leading the way with the biggest growth in total emissions is India, with their emissions growing at about 5% a year, and with a bigger increase this year than last year. Overall total global emissions have increased about 2.7% this year.

The Global Stocktake

At the Paris meeting in 2015, countries made pledges – their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) – to reduce emissions. All of these pledges together are insufficient to limit global warming to below 2 degrees. There is an expectation that countries set new, more ambitious emissions targets every five years, and these revisions are due in 2020. Meetings are taking place in Katowice to discuss how nations are going with mitigation leading up to pledging new targets in two years.

To determine how well countries are going in meeting their NDCs, and therefore how much more they need to cut emissions in their next pledge, their emissions have to be counted and reported. The timing for this periodic Global Stocktake is two years before new pledges are due, and so the first Global Stocktake is happening now at COP24.

Countries have made submissions regarding the actions they have been taking to meet their pledges. However, collecting, interpreting and sharing data takes resources. Some key sticking points in this week’s Global Stocktake negotiations include defining equity, and requests from developing countries for more support in financing, capacity and technology to assist them in being able to report on their emission reduction activities and achievements. So these negotiations have not got very far at this point.

Katowice also provides an opportunity for countries to increase their NDC ambitions, but the word in the endless COP24 corridors is that this is very unlikely. Countries are likely to continue to argue over definitions so that simply coming to an agreement on how to take stock and report progress on current pledges will be an achievement.

Unfortunately, as the Global Carbon Project’s new report shows, even if the negotiators can’t reach agreement on how to count and report their progress on emissions, we already know we’re not on track to meet current pledges and that global emissions are heading in the wrong direction.

Killing the coal renaissance

One of the likely contributors to these recent global emission increases is an expansion of coal-fired power. When mega companies such as Adani decide they can fund their own projects after banks refuse to lend money for them, what is left to stop them?

Insuring Coal No More press briefing at COP24. Image- Prof. Hilary Bambrick

Insuring Coal No More press briefing at COP24. Image- Prof. Hilary Bambrick

Unfriend Coal is working to end the coal industry through an organised campaign to deny coal projects insurance. Similar to the divestment movement targeting banks to not invest in the fossil fuel industry, Unfriend Coal is reaching out to global insurance companies with a request for them not to insure coal projects. Because mines and power stations can’t operate without insurance, the hope is that removing insurance kills the industry: there could be no new projects and existing projects would have to shut down. The Australian Youth Climate Coalition’s (AYCC) Toby Thorpe is involved in this campaign and participated in today’s Insuring Coal No More press briefing at COP24.

Update 4: Air pollution kills

Thursday, Dec 6, 2018

Today WHO launched its Special Report on Health and Climate Change at COP24.

The take home message contained in WHO’s new report is that air pollution kills, and that if we reduce our air pollution emissions in line with the Paris agreement, not only will we limit climate change but we will also save around one million lives every year. Importantly, this one million figure is just the number of deaths that would have been caused directly by exposure to air pollution, not all the lives that would also have been saved by avoiding worsening global warming.

I asked the Director of WHO’s Public Health and Environment, Dr Maria Neira, who led the report launch, to summarise the key messages. You can listen to her response below:

The report examines not only the health benefits of acting on climate change, but the economic gains that come with this. WHO estimates that for every dollar spent on reducing emissions to meet the Paris targets, two dollars will be gained in terms of health benefits. Deep emissions cuts are demonstrably good for the economy because of the positive impact on human health.

recommendations in the WHO report. In Australia, air pollution, mostly from particulates and mostly from coal, kills an estimated 3000 people every year. That’s 3000 very good reasons, aside from limiting future climate change, to make the move to clean renewable energy.

You can download the full WHO report here.

Australia’s emissions targets

One of the anticipated outcomes from Katowice is for countries to become more ambitious in their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), and to set meaningful emissions reduction contributions that give us some hope of staying below the 2 degree threshold. There is not a lot of optimism here though that countries will increase their ambitions at this meeting.

Australia’s current Nationally Determined Contribution is to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 to 26-28% below 2005 levels. It’s an embarrassingly low ambition, especially for a wealthy, high emissions country.

And, Australia has already confirmed that it won’t be announcing any new target in Katowice.

Even with such a paltry target, we’re still nowhere close to meeting it. For the past four years Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions have continued to accelerate.

To meaningfully reduce Australia’s emissions, we need to phase out coal, by shutting down ageing coal-fired power stations and not building new ones.

But we also need to transition away from other fossil fuels: oil and gas. The latest emissions reports show that our rising emissions are at least in part because of gas.

Gas contributes methane emissions. Methane is a more powerful greenhouse gas than CO2 and we’re also not very good at measuring methane emissions.

That means we could be seriously underestimating the contribution that our current gas industry, let alone a future expanded one, is making to climate change.

The gas industry has been very effective at promoting gas as a transition energy source, a ‘least worst’ option, as a necessary step between highly polluting coal and future energy system based on clean renewables.

Once upon a time this might have been a reasonable pathway to take – from coal to gas to renewables – but decades of delay has meant that mitigation action is now much more urgent. The emissions cuts we now need to make have to be deeper and happen more quickly. Thankfully, renewable technologies have also developed over this time and are increasingly affordable, so we can reasonably skip gas altogether and jump straight to clean renewables. Hooray!

Unfortunately, far from being relegated to history as another major contributor to climate change, the gas industry is on the up and up, and with the support of government, particularly via the unconventional means of fracking. WA has recently joined the list of Australian states willing to ignore the need for climate mitigation and frack for gas. And this is despite the fact that fracking is known to be dangerous to the surrounding communities.

Whichever way the gas industry tries to spin it, all fossil fuels are bad for climate and bad for health.

Australia’s increasing emissions and unambitious NDC means we are not even on track to be mediocre. By clinging on to fossil fuels and maintaining such a woeful emissions reduction target, Australia is set to miss the boat on renewable energy innovation.

Update 3: What do young people want from COP24?

Wednesday, Dec 5, 2018

There are a lot of young people here at COP – as volunteers and as presenters. At a session today on ‘Youth demands and expectations of COP24”, four young delegates, from China, Sri Lanka and Seychelles spoke passionately about why they are here and what they hope the outcomes will be.

Here are some of the points they made:

- Half the world’s population is young people. They are the future, they are demanding a place at the table, and they want governments to be held accountable.

- Young people are connecting and collaborating on social media and sharing information about climate change. They see COP as a knowledge sharing opportunity to meet with other young delegates to discuss issues of mutual concern.

- It has been three years since the Paris agreement, and the world has fallen far behind on how to implement it. A rule book on how to proceed with each country’s nationally determined contributions (NDC) to greenhouse gas pollution reduction is urgently needed; if we don’t act before 2030 we don’t get another chance to save the planet.

- These NDCs should be connected to the Sustainable Development Goals

- They are feeling optimistic about how the Katowice negotiations will go and hope that a strong rulebook is agreed to by the participating countries.

- However, they don’t think action can be left solely in the hands of governments.

- The rulebook has to consider the voices of youth, and be inclusive of local communities and considerate of human rights.

Later this afternoon I was privileged to meet a group of school students joining the COP from Tasmania. Toby Thorpe, Harry Tunks, Joshua Hale, and Joshua Rayner were supported by crowdfunding to come to Katowice (L-R in the video below). Toby is with the Australian Youth Climate Coalition.

I asked them what their hopes are for climate change action. You can hear what they have to say here:

As we saw in last week’s School Strike 4 Climate, young people around the world are showing tremendous leadership on climate change.

What else is going on:

There are so many things going on at COP24 and it is impossible to follow even a sizable chunk of it. There are 20,000 people, scores of presentation rooms with concurrent sessions running, press briefings, side meetings, big rooms, little rooms, pavilions for participant countries, booths for NGOs, and hundreds of exhibits. After two days I think I’ve now set foot in most of the wings of this massive venue, a catacomb of temporary buildings and corridors linking more permanent facilities.

This years’ COP24 has attracted 20,000 people. Image – Prof. Hilary Bambrick

This years’ COP24 has attracted 20,000 people. Image – Prof. Hilary Bambrick

As well as getting to presentations and press conferences, I’ve been meeting with the other health observers, linked together via the Global Climate and Health Alliance, to coordinate and plan our activities, and develop common key messages to take to delegates.

In particular, we will be promoting the World Health Organisation’s special report on health and climate change which will be launched on Wednesday, and sharing key messages from last week’s Lancet global Climate Countdown report and the associated country reports, including Australia’s.

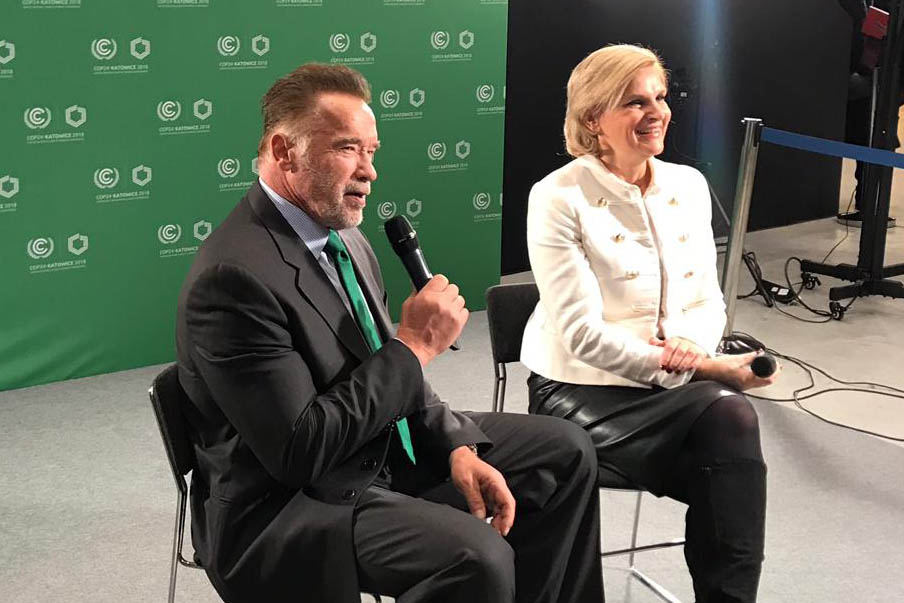

Former Governor of California, Arnold Schwarzenegger speaking with WHO’s Dr Maria Neira at COP24. Image- Prof. Hilary Bambrick

Former Governor of California, Arnold Schwarzenegger speaking with WHO’s Dr Maria Neira at COP24. Image- Prof. Hilary Bambrick

This is the first time that ‘health’ has had much of a profile at COP, with support from the former Governor of California, Arnold Schwarzenegger. In his conversation today with WHO’s Dr Maria Neira, the focus was on what should be a no-brainer – that if we tackle air pollution we not only limit future climate change but we also improve the health of millions of people, today.

Update 2: Katowice & Coal

Tue, Dec 4, 2018

Katowice is a city of around 300,000 people, located 300km southwest of Warsaw. It’s pretty chilly here, with the daily temperature range hovering a few degrees either side of zero. As a snow-deprived Queenslander, I’ve been hoping to see some of the white stuff, but so far it’s just been rather soggy.

Katowice is the capital of the wealthy Silesia region which has been the economic powerhouse of Poland because of coal mining. Poland now sees the climate and economic benefits of moving away from coal and, as host of COP24, is looking to drive discussion on how best to ensure a “just transition” for coal mining regions everywhere.

Bełchatów Coal Mine in Poland, Kamil Porembiński (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Bełchatów Coal Mine in Poland, Kamil Porembiński (CC BY-SA 2.0)

A “just transition” means making sure that coal workers and coal mining communities aren’t left behind in the new energy economy, that we can transition away from a dependence on coal without adverse social and economic consequences. It means making explicit, positive plans for the future of people and communities who would otherwise likely lose their livelihoods as coal is phased out. It means caring for workers and their families.

Currently, coal provides 80% of the energy mix in Poland, with carbon-neutral sources (hydro and wind) contributing about 18%. Poland plans to halve the contribution of coal in just a decade, to 40% by 2040.

Keen to rapidly transition away from coal, Poland is advocating for the costs of transition to be shared across European Union countries. With a GDP per capita of only about 40% of the EU average, Poland is seeking the establishment of a dedicated EU fund to assist coal-intensive regions, such as Silesia, to transition so that the cost of transition to reduce global greenhouse gas pollution is not unfairly placed on lower GDP countries.

A just transition away from coal should be a priority for Australia too. We have several communities that have been built on coal mining and coal-fired power generation, and we now need to look to other ways of ensuring their future prosperity now that demand for coal is, rightly, on the decline.

Moving away from coal will not only assist in reducing emissions, but has direct and immediate health benefits by eliminating a major contributor to air pollution, including in Australia.

How each coal mining community and its workers will best transition away from coal will depend on their circumstances. It might mean any or all of retraining workers and/or providing a jobs guarantee, or investment in regional manufacturing to support clean renewable technology, or the development of sustainable agriculture, tourism, or other industry in the region.

Hazelwood open-cut mine burning in 2014. Image- Keith Pakenham/CFA

The town of Morwell in Victoria, for example, is set to become a manufacturing hub of electric cars following the massive Hazelwood mine fire and subsequent closure of the mine last year. This new industry is expected to provide 500 jobs in Morwell.

However transition is to be managed, affected communities have to drive the change that’s right for them, with the support of government and the private sector.

The death of the coal industry is inevitable and indeed necessary if the world has any hope of limiting climate change. A planned, well-managed transition from coal is entirely possible, and will protect the livelihoods and wellbeing of workers and their communities.

Arnold Schwarzenegger speaks at COP24. Image – Prof. Hilary Bambrick

Arnold Schwarzenegger speaks at COP24. Image – Prof. Hilary Bambrick

Some highlights from Day 1 of COP24

- David Attenborough urging climate action to avoid the collapse of civilisations and mass extinction

- Arnold Schwarzenegger naming climate change as a people’s issue and a health issue. He discussed the need to reduce meat consumption to reduce agricultural emissions, the role of climate change in California’s recent record-breaking fires, and how air pollution from burning fossil fuels is killing people here and now. He noted that transitioning to renewables would save 7 million lives a year.

Update 1: What is COP24 and why is it important?

Mon, Dec 1, 2018

You will have heard of the Paris Agreement, where governments around the world signed up to limit global warming to 2 degrees Celsius, with an aspirational goal of not surpassing 1.5 degrees. This agreement was the result of the COP21 negotiations in 2015. Since then, we’ve had COP22 (Marrakech, Morocco) and COP23 (Bonn, Germany), and now COP24 is happening in Katowice, Poland, December 3-14.

‘COP’ stands for ‘Conference of the Parties’, and refers to the annual meetings held between participants in the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). The very first COP meeting was held in 1995 in Berlin. While national governments are the negotiating participants at these conferences, a number of intergovernmental and non-government organisations are permitted as ‘observers’.

COP21 in Paris, which resulted in the signing of the Paris Agreement.

COP21 in Paris, which resulted in the signing of the Paris Agreement.

The world has already warmed 1°C since mass industrialisation with serious impacts on human health from worsening extreme weather events, such as heatwaves, bushfires and flooding, and the spread of vector-borne diseases, such as malaria. And the greenhouse gas pollution we have already released means the world will warm a further half a degree or so over the next couple of decades, even if we stopped burning all fossil fuels today. This is because our climate system is massive and slow, like a giant tanker, and so the warming effect from released emissions is somewhat delayed. This means that from this moment, we are more or less locked in to the aspirational target agreed to at Paris, which makes it all the more urgent to slam the brakes on emissions fast.

COP24 in Poland is important because it aims to establish a rulebook for climate action, including the ratcheting up of emission reduction targets to accelerate the transition from fossil fuel dependence and into a clean and renewable energy world. It will also seek agreement on how countries set their targets and on how to measure whether these targets are achieved.

COP24 opening plenary in Katowice, Poland © cop24.gov.pl

COP24 opening plenary in Katowice, Poland © cop24.gov.pl

At COP24 in Katowice it will, however, certainly be a challenge to get global agreement on how to go about meaningful greenhouse gas reductions. Australia is lagging behind the rest of the world, despite being blessed by wealth and technological capacity to develop our abundant renewable energy resources. For the past three years our greenhouse gas emissions have actually increased. Failure to act now will have devastating consequences for our children and future generations.

This is not a world that is compatible with healthy populations. It will be a world of frequent extreme weather of unimaginable intensity, of increasing disorder, war and civil conflict, of vast inequities, a world of hunger, disease and poverty. It is a world that may not be compatible with human life at all.

But the solutions are available and are both technically and economically feasible. We need to accelerate the transition to renewables and storage technologies and ramp up other climate solutions across all sectors of the economy.

About the author:

Hi, I’m Hilary. I’m a Climate Councillor and Professor of Public Health at Queensland University of Technology. My background is environmental epidemiology and bioanthropology, which basically means I study how the environment affects our bodies and how we interact with our environment. I’ve been researching climate change and health for 20 years.

Hi, I’m Hilary. I’m a Climate Councillor and Professor of Public Health at Queensland University of Technology. My background is environmental epidemiology and bioanthropology, which basically means I study how the environment affects our bodies and how we interact with our environment. I’ve been researching climate change and health for 20 years.

My work looks at how climate change is affecting the health of populations and what we need to do to adapt to climate change to protect our health. From small communities to entire nations, I work on how we may best strengthen our resilience to the challenges of climate change into the future.

My research has taken me to some of the most beautiful and climate-fragile places in the world, including Ethiopia, Kiribati, Samoa, Cambodia, Laos, and Timor-Leste. Seeing first-hand the damage that climate change is already doing to communities and to people’s health and wellbeing means I am highly aware of how urgently we need to act to meaningfully reduce our greenhouse gas pollution and limit climate change.

When I first started working on climate change, we used to talk about its impacts as happening in the future — but not anymore. We can see that climate change is already affecting real people and real communities in real time, in Australia and around the world.

One of the approved observer organisations at this year’s COP is the Climate and Health Alliance (CAHA), and it is as a representative of CAHA that I am able to attend COP24 in Katowice. CAHA is an Australian NGO that works to raise awareness of the impacts of climate change on health and develops strategic policy to minimise poor health outcomes associated with climate change. You can read more about the work of CAHA here.