This piece was written by Climate Councillor Greg Mullins, and originally appeared in the Sydney Morning Herald on July 30, 2020.

A week before Christmas last year, five of my fellow veteran fire and emergency chiefs and I held a press conference as fires ravaged Australia’s east coast. Appalled by the utter lack of leadership from Canberra in supporting bushfire response efforts, we took matters into our own hands.

We announced that 33 retired fire and emergency chiefs would convene a National Bushfire and Climate Summit to do what the federal government should have done: bring together everyone with a role to play in an effective bushfire response, and develop solutions to help protect Australians against the growing bushfire threat, fuelled by climate change.

Much has changed since then. The COVID-19 pandemic has turned life as we know it on its head, forcing us to take our summit online, but it did not change our commitment to finding solutions to improve Australia’s bushfire response, readiness, and recovery.

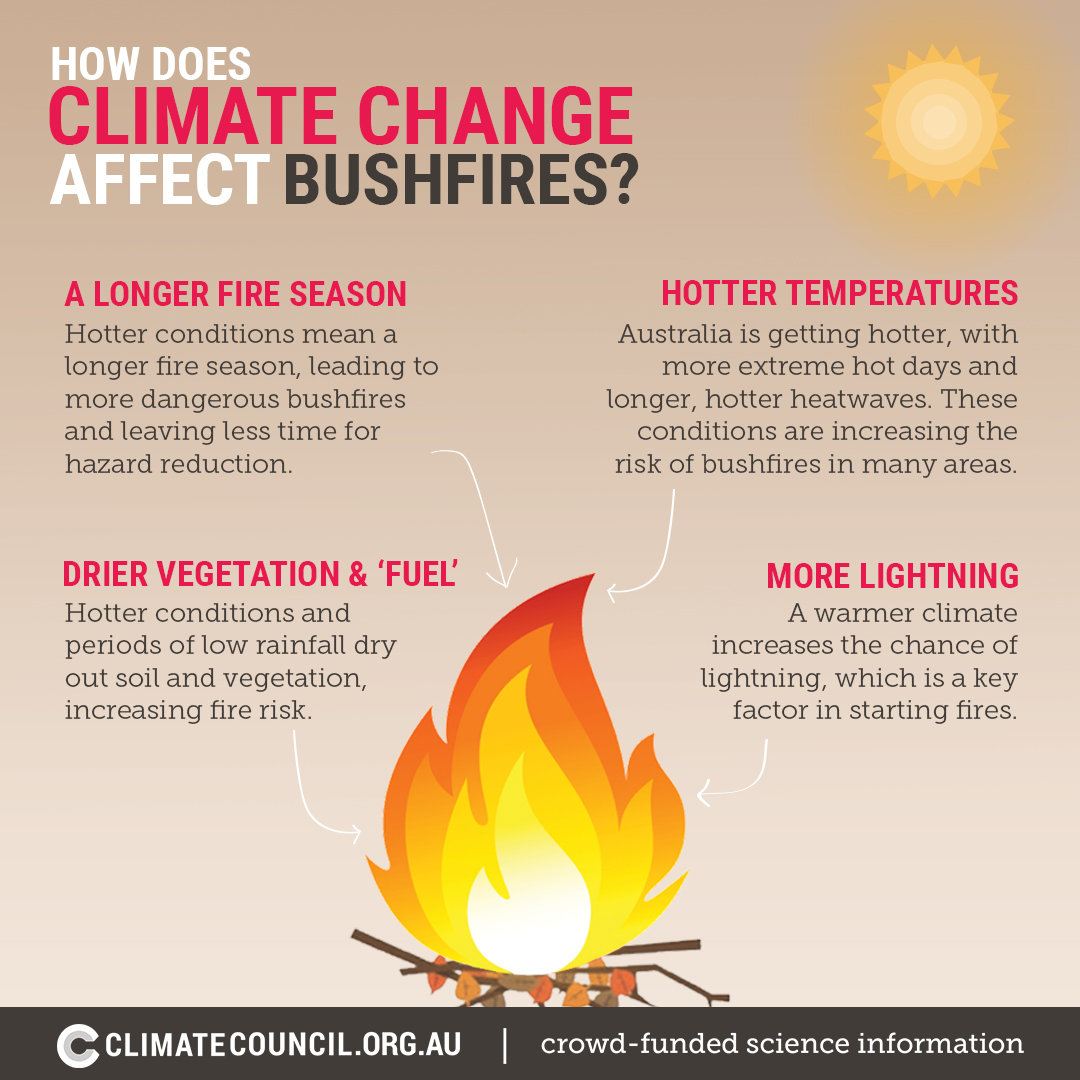

Our sense of urgency was fuelled by a simple truth that was echoed time and again in every session: climate change has pushed Australia into a new era of unprecedented bushfire risk, and our governments have underestimated the threat. This puts communities in danger.

The concern we felt was mirrored in the discussions at the summit, which brought together almost 200 experts including firefighters, bushfire survivors, economists, doctors, farmers, Indigenous cultural burning experts, economists, and many more.

In every session, there was a shared, palpable level of fear. Fear that the death and destruction of our Black Summer is now the benchmark for our periodic worst fire seasons. Fear that no matter what we do to fight such fires, fire seasons like our last will overwhelm every effort at control. Fear that some communities are now located in places that cannot be defended on the worst days. Fear that old approaches to fuel management are no match for fires that now burn so fast and intensely that they create their own dry thunderstorms and weather systems.

The biggest fear expressed, however, was that our national government will continue to ignore the urgent need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and act on climate change, while supporting the opening of new fossil fuel projects that will worsen global warming.

The truth is abundantly clear: we need a fundamental rethink of how we plan, prepare for, respond to and recover from bushfires. Our Australian Bushfire and Climate Plan, with 165 practical recommendations resulting from summit discussions, is a good start.

But first, if we are to have any hope of coping with the increasing bushfire threat, we must deal with the underlying driver – by phasing out fossil fuels, banning new coal, oil, and gas projects, and reaching net zero emissions as fast as possible.

The remaining recommendations outline how we can better use the support capabilities of our defence forces, better resource our fire, emergency and land management agencies, increase fuel reduction, resource Indigenous cultural burning capabilities and improve insurance access. We also need a national strategy to deal with the health consequences of worsening bushfires.

Greg Mullins, Lee Johnson, Craig Lapsley, Mike Brown, Naomi Brown, Peter Dunn – Emergency Leaders for Climate Action.

We recommend new rapid fire-detection technology, new types of water-bombing aircraft and more remote-area fire teams to stop small fires becoming big ones.

There is also considerable emphasis on community support, and community-led solutions. This includes boosting mental health support for afflicted communities and firefighters, and community resilience hubs in every vulnerable local government area.

It is an ambitious plan, for a big problem, but who will pay for it? The summit concluded that fossil fuel companies, which drive the emissions-causing global warming and extreme weather, should pay a levy so Australia can build resilience to, and recover from, worsening climate disasters.

We have seen the federal government act quickly and decisively to respond to the COVID-19 crisis.

Australia needs to flatten our emissions curve with the same sense of urgency. As we all experienced last summer, climate change is also a matter of life and death for Australians – not to mention the multi-billion-dollar economic costs of past climate inaction.

As we share our plan with the Prime Minister, premiers and chief ministers, the royal commission and state bushfire inquiries over the next few weeks, we are aware that we are in the midst of an escalating global climate emergency, and the time for life-saving action is running out.

Greg Mullins is the founder of Emergency Leaders for Climate Action. He is a Climate Council councillor and former commissioner of Fire and Rescue NSW.

This piece was originally published in the Sydney Morning Herald on July 30, 2020.