With a La Niña event now well underway, Australia’s summer 2020/21 is looking at above-average rainfall for many parts of the continent, bringing elevated risk of flooding. As of December, we are already seeing this exemplified with intense rainfall down the east coast. Fast-moving grass fires are also a risk in some areas, especially in NSW (west of the Great Dividing Range), as new growth dries out in the warmer weather.

This summer is being shaped by an altogether different set of climate drivers than the Black Summer of 2019/20, and is likely to feel very different for many of us, but is already bringing challenges of its own.

This explainer gathers together the latest advice from the Bureau of Meteorology and the Bushfire and Natural Hazards Cooperative Research Centre on what to expect through the rest of the summer. It takes stock of the extreme weather risks, takes a close look at La Niña – the dominant climate driver affecting our weather at the moment – and puts it all in the context of our changing climate.

Stay safe everyone, and if you haven’t already done so, check your state/territory’s fire and emergency agency for advice on how to manage the summer’s extreme weather risks.

What is La Niña, and how is it shaping the 2020/21 summer in Australia?

On 29 September, the Bureau of Meteorology declared that a La Niña was underway. Australia’s weather is influenced by a number of “climate drivers”, including the El Niño Southern Oscillation, Indian Ocean Dipole, Southern Annular Mode and Madden-Julian Oscillation. These are cyclical fluctuations in ocean surface temperatures and ocean-atmosphere interactions in the Pacific, Indian Ocean, Southern Ocean and the tropics respectively. They influence year-to-year variations in temperature, rainfall and other weather patterns.

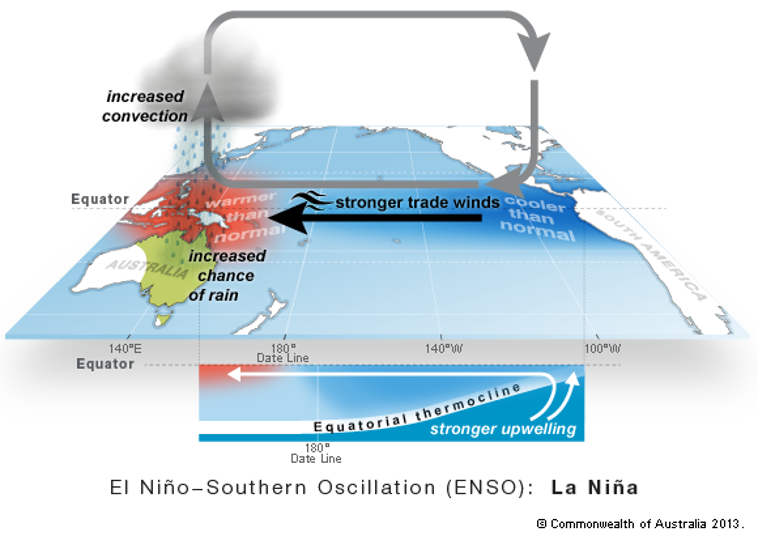

La Niña is one phase of the El Niño Southern Oscillation. It occurs when equatorial trade winds become stronger, bringing cooler water up from below. This results in a cooling of the surface of the central and eastern tropical Pacific Ocean. The enhanced trade winds also help to accumulate warm surface water in the western Pacific and to the north of Australia. These warmer waters in the western Pacific mean more cloud develops as warm, moist air rises. This can mean heavy rainfall to the north of Australia.

Pacific Ocean – La Niña. Source: Bureau of Meteorology.

La Niña events are associated with wetter years for much of the continent. However, every La Niña event is different, as the effects of La Niña may be amplified or dampened by the other climate drivers. Indeed, while a La Niña was declared back in September, it wasn’t until later in the year that we began to experience typical La Niña conditions.

As well as more rainfall across eastern, central and northern Australia, La Niña is also associated with cooler daytime temperatures south of the tropics, and a greater number of tropical cyclones.

The current La Niña is expected to persist until at least January 2021. Some models suggest it could reach a similar strength to the La Niña of 2010-12. That La Niña event was particularly intense and long-lasting and coincided with Australia’s wettest two-year period on record. It saw devastating floods in Brisbane and elsewhere. However, there are reasons to expect that this current La Niña will not be as disruptive as the event of 2010-12, including the fact that the 2010-12 La Niña coincided with a negative phase of the Indian Ocean Dipole, which tends to amplify the effects of La Niña. The Indian Ocean Dipole is currently in a neutral phase.

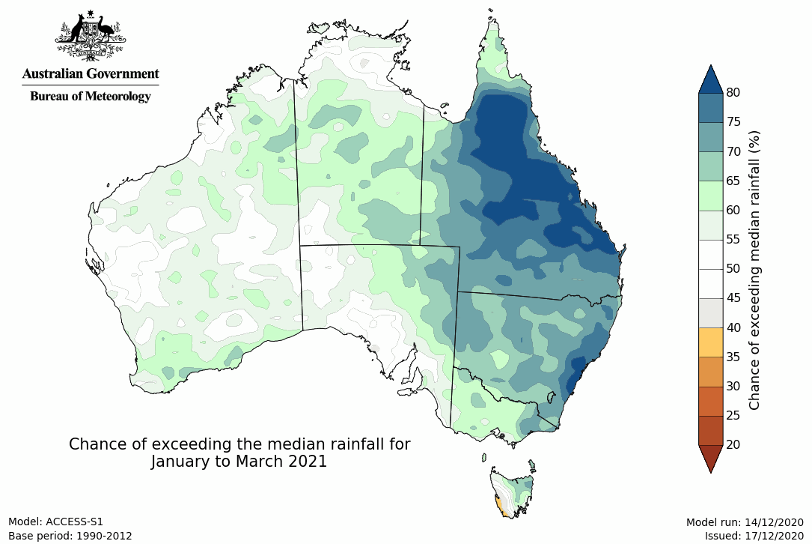

According to the Bureau of Meteorology’s most recent climate outlook, and consistent with typical La Niña conditions, rainfall for January through to March is likely to be above average for eastern and northern Australia, particularly eastern parts of Queensland and NSW. Maximum temperatures are likely to be above average for Tasmania, Victoria, far west Australia, and along the northern and eastern coastlines. Minimum temperatures are very likely to be above average across much of Australia.

The probability of exceeding median rainfall for January to March 2021. Source: Bureau of Meteorology.

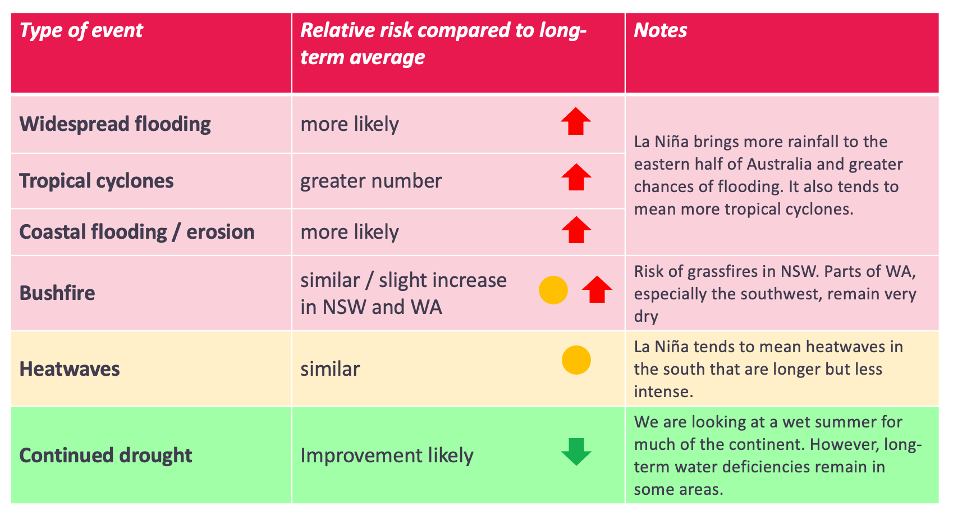

What extreme weather risks are we looking at this summer?

Above average rainfall for eastern and northern Australia, and in particular the eastern parts of Queensland, means elevated risk of widespread flooding for these areas. Sadly, December has already seen communities along much of the coastal northern NSW and southern Queensland experienced a series of intense rainfall events, leading to significant flooding.

In terms of cyclones, during La Niña there are typically more cyclones in the Australian region than during non-La Niña years. The 2010-12 La Niña saw several notable cyclones, including Cyclone Yasi – one of the strongest and costliest in Australia’s history. The only years during which there have been more than one severe landfalling tropical cyclone in Queensland were La Niña years. The Bureau of Meteorology has predicted an average to slightly-above-average number of cyclones for the 2020-21 season.

Summary of extreme weather risks for the 2020-21 summer. Adapted from the Bureau of Meteorology’s Summer Outlook webinar.

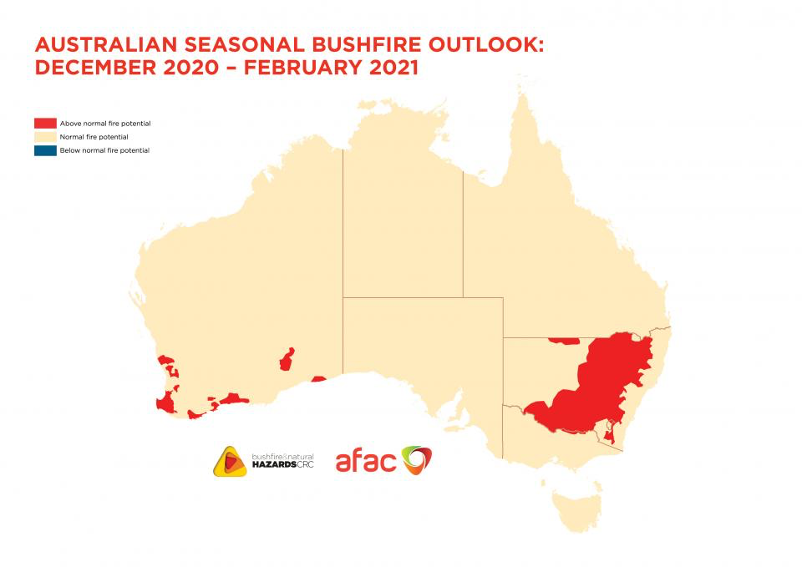

What does it mean for bushfire risks?

Above-average rainfall may seem like good news when it comes to bushfires. However, rain over spring and early summer means lots of grass growth. This can then dry out quickly in the warm weather and mean risk of fast-running grass fires.

The latest seasonal bushfire outlook from the Bushfire and Natural Hazards Cooperative Research Centre (December-February 2021) shows above normal fire potential in NSW, west of the Great Dividing Range, due to risk of grass fires. (Figure 4.) Parts of southern Western Australia also have above normal fire potential, though for a different reason, as these are among the few parts of the country to have missed out on significant rainfall in 2020.

All in all, 2020/21 is unlikely to see a repeat of the horrendous scenes we saw over the Black Summer, though we must not be complacent. Sadly, with climate change we have entered a new era of greater fire risk, and must be even more vigilant than before. Be sure to check out the fire authority in your state or territory for the latest information.

Australian seasonal bushfire outlook, December 2020 to February 2021. Areas in red are areas experiencing above normal fire potential. Source: Bushfire and Natural Hazards Cooperative Research Centre.

And how does it all relate to climate change?

While the La Niña event is having a significant influence on our weather this summer, it is important to remember that these short-term cyclical drivers are now occurring in the context of a warming climate.

Despite the fact that La Niña tends to bring cooler temperatures, Australia recorded its hottest spring and November on record. A spring as hot as what we’ve just experienced would have been virtually impossible without climate change.

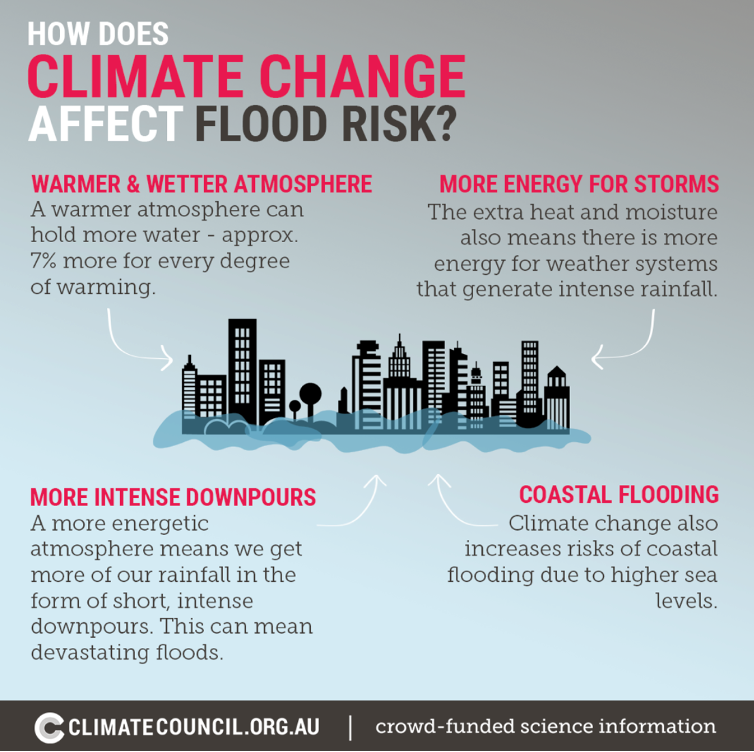

All weather is now occurring in an atmosphere that is getting warmer, wetter and more energetic.

A warmer atmosphere can hold more water vapour – approximately 7 percent more for every degree of warming. A warmer and wetter atmosphere also provides more energy for weather systems that generate intense rainfall. This means that while climate change may mean only a modest increase in the overall amount of precipitation globally – limited by the moisture holding capacity of the atmosphere – it is leading to a marked increase in the heaviest and most damaging precipitation events. In other words, we are getting more of our rain in the form of extreme downpours.

Climate change is increasing the likelihood of the kind of intense rainfall events and destructive storms that we have seen wreak havoc along the northern NSW and southern Queensland coast so far this summer.

“The sort of conditions that spawn violent storms like this are becoming more frequent due to climate change, because you have more heat and energy in the atmosphere.” Climate Council expert, Professor Will Steffen.

In addition, rising sea levels due to climate change means that storms are riding upon higher seas.

An infographic depicting the influence of climate change on flood risk.

Stay safe everyone! We’ll see you in 2021. It’s going to be an absolutely critical year for action on climate change, and we are ready!